The Ethics of Economic Metaphors (Introduction)

How our metaphors shape the way we think—and how the drift of Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” reveals the need for clarity, humility, and honest speech in public life.

👉 This is the introduction to my 9-part series The Ethics of Economic Metaphors.

👉 You can read all parts here → (link coming soon)

A Gentle Welcome to the Conversation

Small Lanterns for a Big World

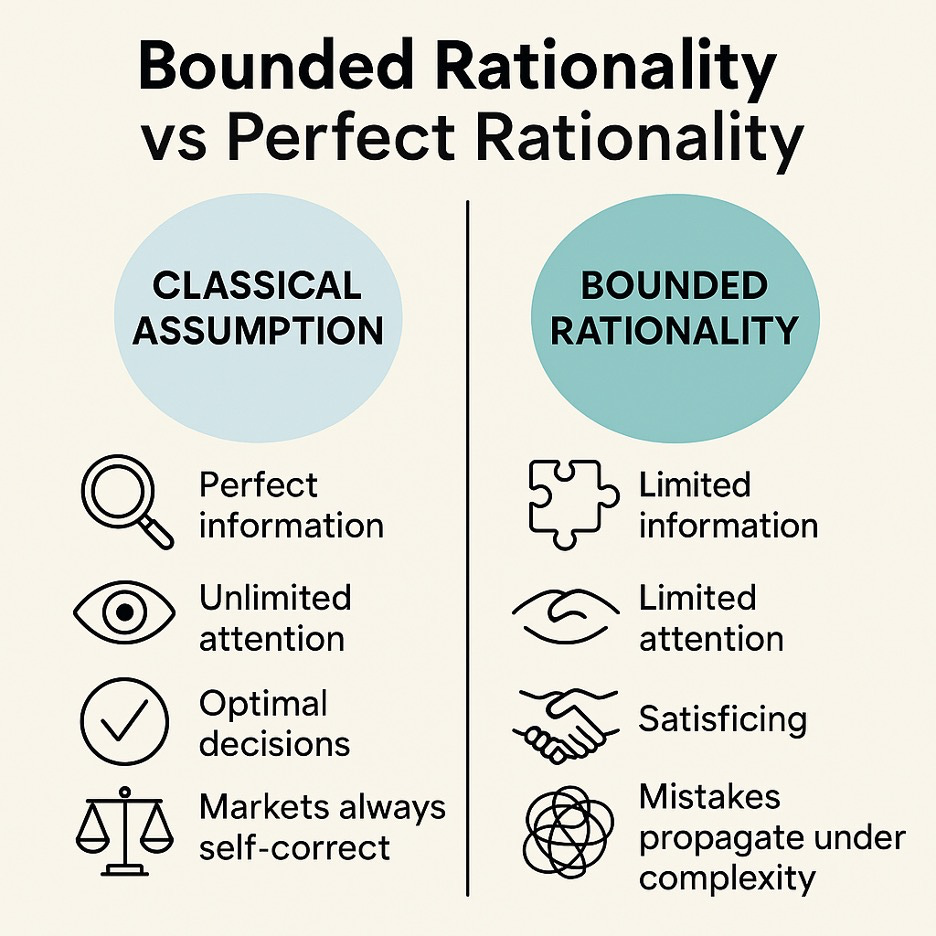

Humans have bounds in reason. We humans like to imagine ourselves as clear-eyed thinkers, carefully weighing every fact the way a jeweler studies a diamond. But the truth—spoken softly, the way an elder might say it over evening tea—is that our minds come with natural limits. We see the world through narrow windows, not grand, sweeping vistas. Our attention flickers. Our memories blur. Our understanding arrives in pieces.

It’s no insult; it’s simply the condition of being human.

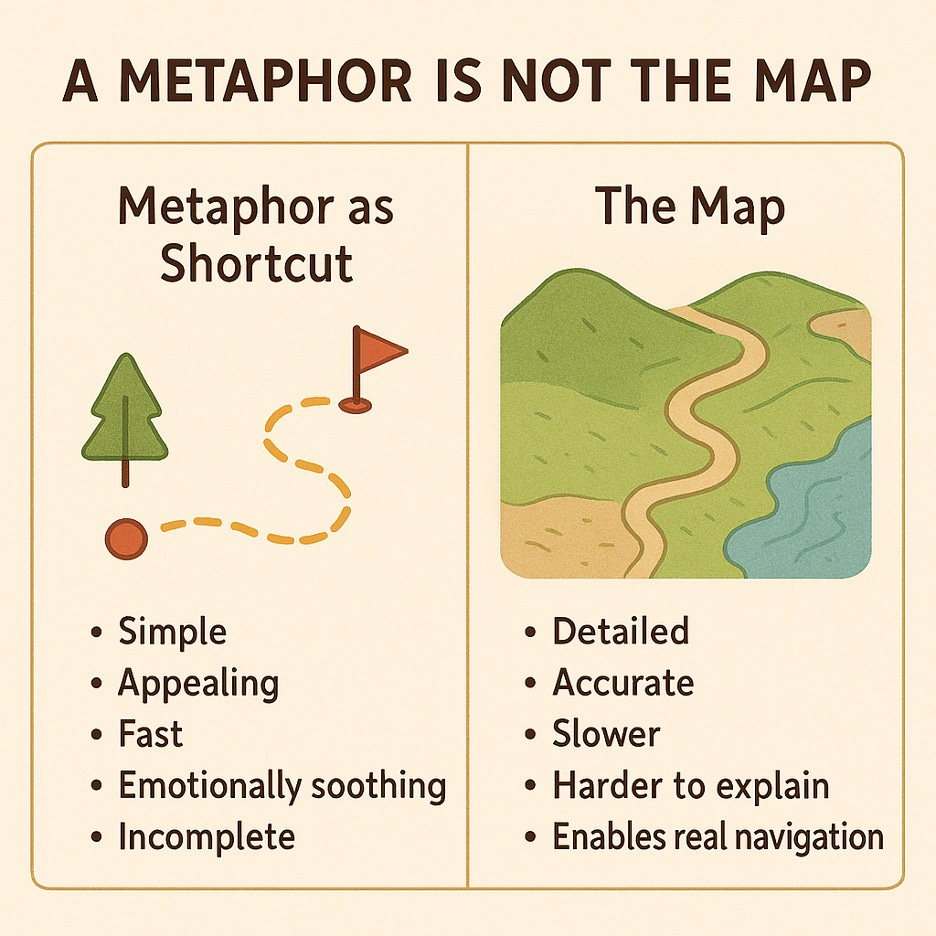

To make sense of this vast, tangled world, we reach for words and metaphors—little lanterns we hold up in the dark to illuminate what we cannot fully grasp. Every age has had its favorite lanterns. They help us see a pattern, a possibility, a story. But metaphors can only light a portion of the path. They can guide us, or they can mislead us, depending on how faithfully we remember their limits.

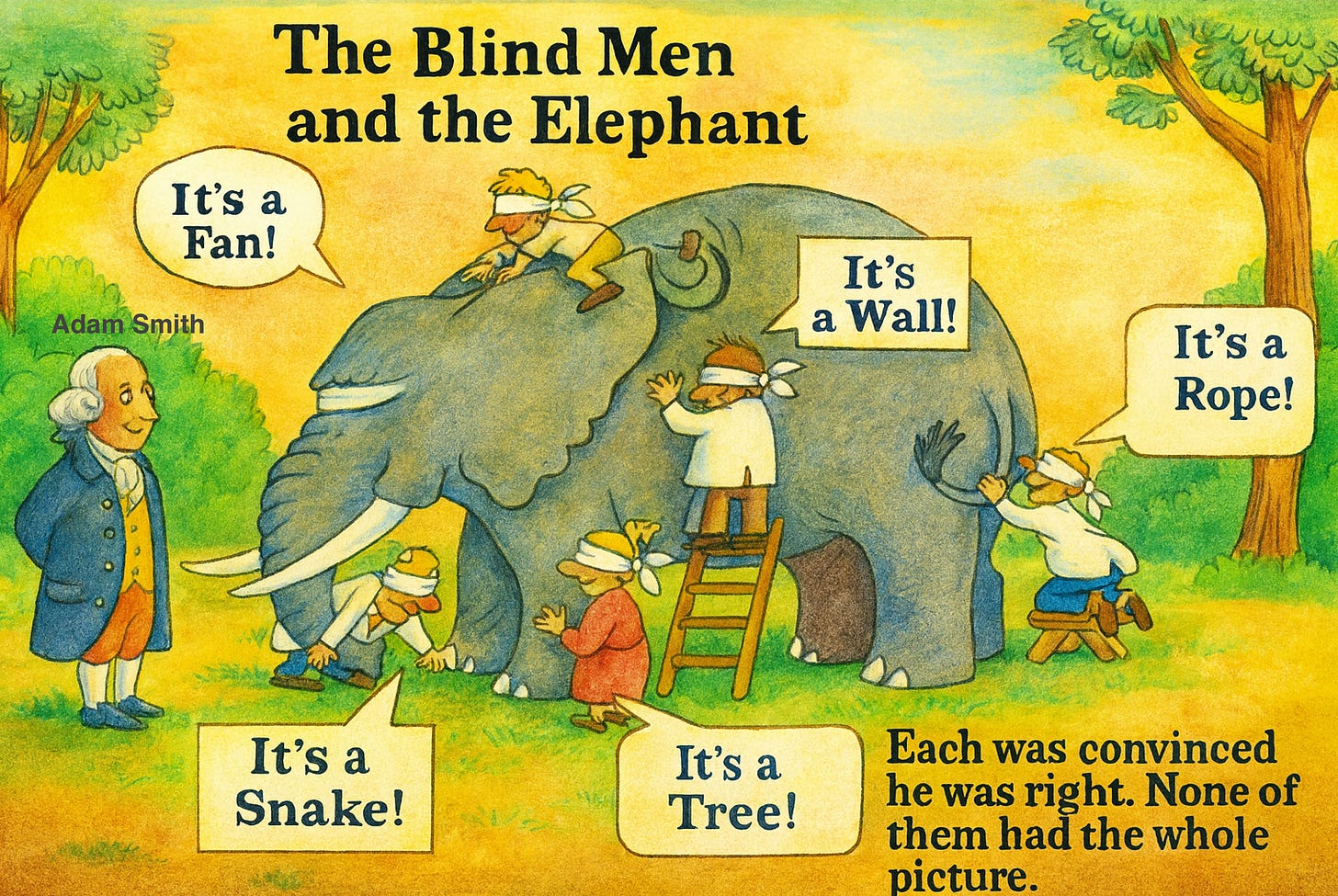

It’s like the old parable of the blind men and the elephant: one feels the trunk and calls it a snake, another the leg and calls it a tree, another the ear and swears it’s a fan. None of them are wrong; none of them are entirely right. Each is simply describing the part they can touch. In this way, all of us—scholars, citizens, presidents, prime ministers—are blind men with different pieces of the same animal.

This is the heart of the philosophical problem:

we build our societies, our policies, and even our moral convictions on understandings that are always partial.

Because of this, leaders carry a special ethical burden. Not to pretend they see perfectly, but to remember that they don’t. Not to cling to metaphors as doctrines, but to use them lightly, humbly—aware that a metaphor can illuminate life or distort it, depending on how firmly one grips it. The work of politics, at its best, is not to turn symbols into dogmas, but to steward them responsibly, with the gentleness of someone handling something that does not fully belong to them.

Human rationality is bounded—by time, by emotion, by experience, by the simple fact that no one can hold the whole elephant at once. Yet within those bounds, we do our best. We grope for understanding, we imitate those we trust, we lean on habits when our minds are tired, and we reach for stories when the world grows too large.

And so this essay begins with a simple recognition:

before we speak of markets, governments, or grand theories, we must speak honestly about the human mind—its limits, its metaphors, and the shared responsibility we have to navigate a world far greater than our own understanding.

From there, everything else follows.

The Heart of This Essay

How We’ll Walk This Path Together

There is an old saying that when we do not yet know the whole landscape, it is wise to walk slowly, lantern in hand. This multi-part series follows that kind of path.

To explore our shared responsibility as thinkers, citizens, and policy-makers, I turn to one familiar economic image—the old “invisible hand.” Not to argue, not to win points, but simply to use it as a gentle case study. Together, we will look at how metaphors help us see, how they sometimes lead us astray, and why anyone working in public life must handle them with humility.

Ideas Along the Way

Human cognition is bounded.

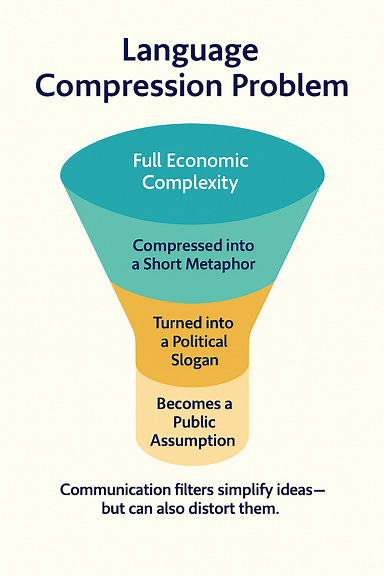

Our attention, memory, and perception can only take in pieces of a much larger world. Because our understanding is fragmentary, we lean on words, stories, and metaphors to help us navigate—though these tools illuminate only part of the truth and can mislead when treated too literally.Metaphors shift over time.

Their meanings stretch and drift, sometimes right under our feet, whether we notice or not.Every metaphor has honest limits.

It works well in some places and not in others. Ignoring these boundaries invites confusion, and sometimes harm.An economic metaphor is not the map.

And a metaphor is not the territory. It can guide, but it cannot replace careful thought.Our systems cannot escape our limitations.

Because human beings are imperfect and bounded, the systems we create will always carry the same marks. Imperfect beings cannot create perfect systems.

I will be using Adam Smith’s old metaphor of the “invisible hand” as a simple lantern to help light the path of my argument about how metaphors shape our understanding.

Political leaders, economists, and public figures across eras have invoked the metaphor of the “invisible hand” to support competing narratives: some treat it as evidence of market harmony, others as a myth that obscures the need for institutional guidance.

But here’s the gentle truth: Adam Smith used the phrase only once in The Wealth of Nations, and not at all in the sense it is often told today. My aim is simply to clear up that misunderstanding, not with scolding but with clarity.

We clear ideological noise and return to first principles—specifically, to examine what Adam Smith actually wrote about markets, morality, and the institutional conditions that make economic systems function well.

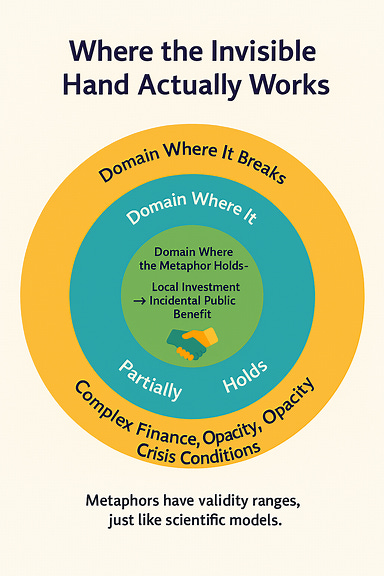

Smith used the “invisible hand” only once in The Wealth of Nations, describing a specific case in which merchants’ preference to invest domestically—out of caution, not ideology—incidentally benefited the nation; it was a contextual observation, not a universal economic law.

Smith envisioned markets functioning within a moral and institutional framework: the state had essential duties—defense, education, justice, infrastructure, financial regulation—that markets alone could not fulfill. For him, freedom required guardrails, and the alignment of private and public interest depended on ethical constraints, not on invisible mechanisms.

Smith’s “invisible hand” was originally a narrow, context-specific metaphor, but over time it was expanded—particularly in the twentieth century—into a broad doctrine suggesting that self-interest reliably produces social harmony, a meaning Smith himself never endorsed.

When we lean too heavily on metaphors or misquote great thinkers, it may be a small warning sign that our own thinking has grown thin. And thin thinking carries consequences.

History has shown—especially in the years leading up to the Financial Crisis of 2008—that ideas built on shaky assumptions can ripple outward into very real human suffering.

Solutions

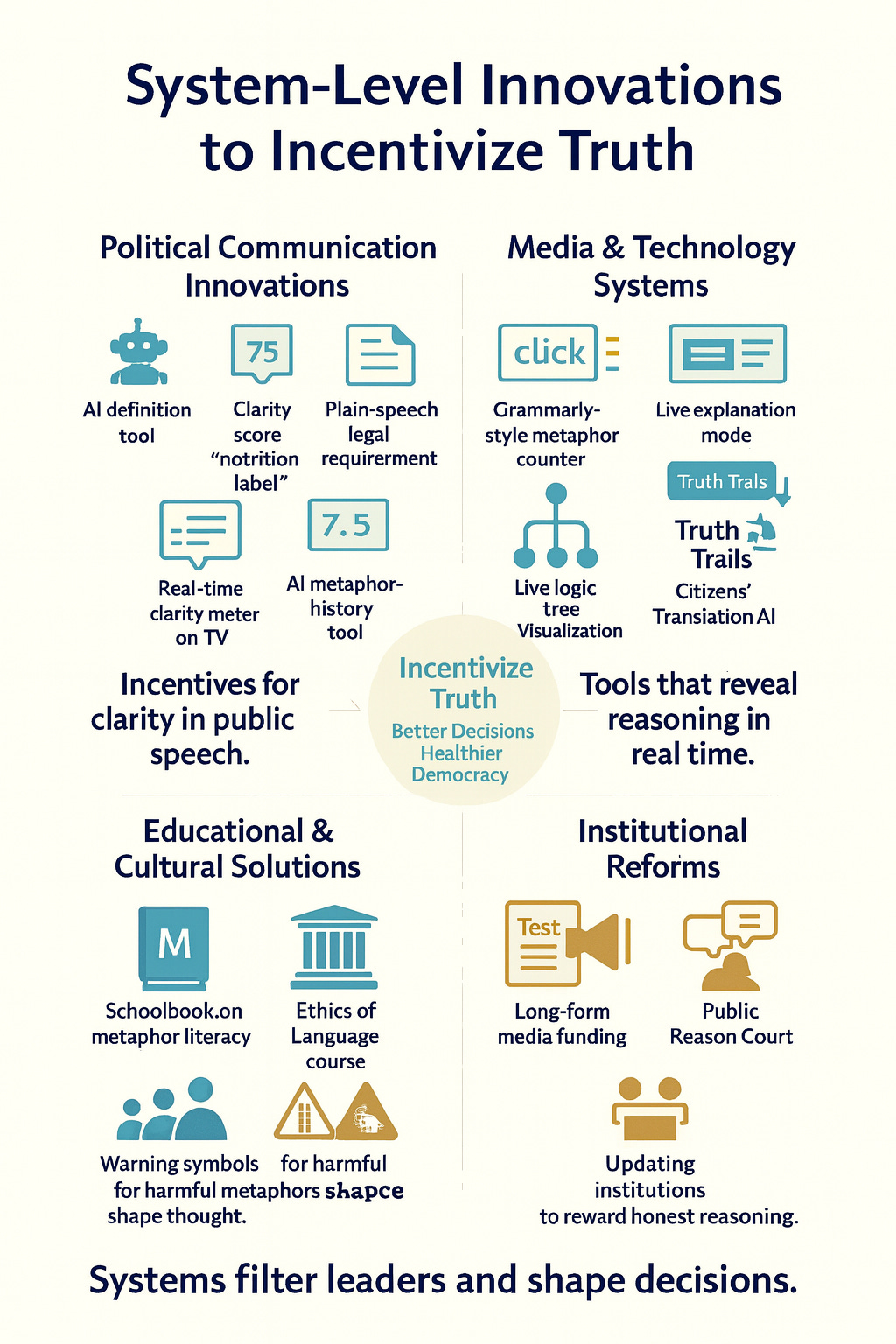

At the end of this essay, I present some small seeds for improving systems that shift incentives for truth—through AI tools, plain-speech requirements, real-time clarity metrics, and educational reforms—societies can gently steer public discourse toward concrete definitions, explicit reasoning, and transparent argumentation. Better incentives yield better speech, which yields better choices.

What This Essay Is Not About

Before we walk any farther, it may help to pause and set down a few things this multi-part series is not trying to do. Clarity, after all, is an act of kindness. Naming what is outside our purpose lets the reader settle in without worry.

This essay is not a fight with anyone—not with economists, not with business, not with Adam Smith, and not with the people who carry these ideas into public life. Its aim is gentler than that.

To keep things plain:

It is not an argument for or against any economic ideology.

No system is being championed or condemned here.It is not really about the invisible hand, self-interest, capitalism, or business at all.

Those ideas appear only as familiar resting spots along the way—helpful examples, not battlegrounds.It is not a criticism of politicians or policy-makers.

Most people in public life are doing their best with the information they have.It is not a claim that human beings are foolish or incapable.

Our limitations are simply part of our shared humanity, not moral failings.It is not a case for or against Adam Smith.

Smith is simply a companion for our walk—someone whose ideas help us think more clearly.

The Heart of the Matter

The root of all this lies somewhere quieter, closer to the ground.

It lies in the way the human mind works.

Because our minds are limited—bounded by attention, time, emotion, and the simple need to make sense of things—we reach for metaphors as shortcuts. They soothe us. They organize experience. They help us hold ideas that are too large to grasp in full. And as the years pass, these metaphors shift and grow, just as living language always does.

None of this is wrong.

But in economics, politics, and public decision-making—where the well-being of real people is at stake—these shifts matter. They ask us to move with greater care, to do our due diligence, to design systems that encourage fuller explanations rather than quick slogans. They remind us not to rely on stamped names from the past, or on the certainty of any single voice.

A Call for Clearer Thinking

At its heart, this essay is about intellectual honesty.

It is about remembering that words change through history, sometimes even reversing meaning, and that these changes shape how we think and how we govern. It is a reminder that in a complex world, good decisions depend on clear premises, careful reasoning, and humility about what any one of us can know.

In short, this essay is an invitation—to think a little more slowly, a little more kindly, and a little more deeply about the metaphors that guide our public life.

🌿 Series Navigation

(Links coming soon)