The Ethics of Economic Metaphors: The Limits of Reason (Part 1)

A gentle look at why our minds reach for metaphors when the world grows too complex.

Series Note:

👉 This is Part 1 of my series The Ethics of Economic Metaphors.

👉 You can read all parts here → (link coming soon)

Why We Speak in Pictures

Long before we built cities or wrote laws, we had words. We used them the way a traveler uses walking sticks—something to steady us as we move through a world far bigger than we can fully understand. Words are how we point at the mysteries around us and say, “Ah, perhaps it’s a little like this.” They are our first tools for taming confusion.

Among all the tools language gives us, metaphors are the most humble and the most human.

A metaphor is when you describe something by saying it is something else, to help your mind picture it better.

For example:

“My room is a jungle” doesn’t mean there are real trees — it means it’s messy.

“He has a heart of gold” doesn’t mean his heart is metal — it means he’s very kind.

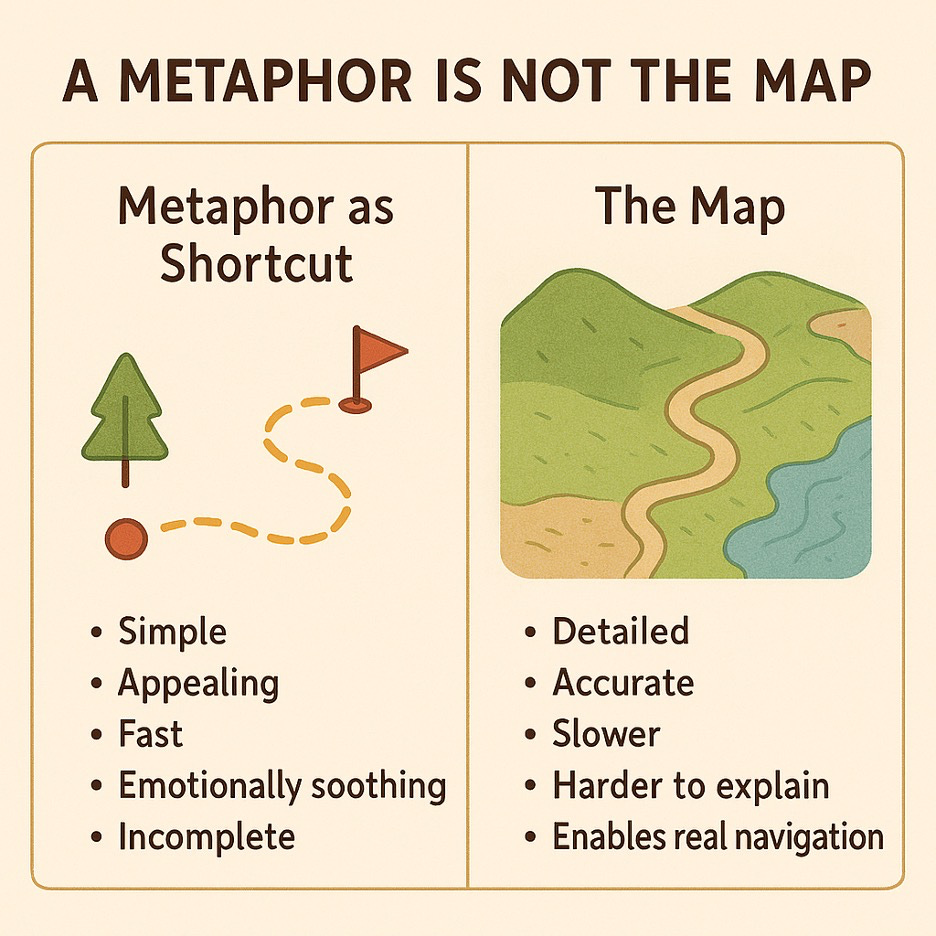

A metaphor is like using a little shortcut for your imagination. It helps you understand something by comparing it to something you already know.

A metaphor is simply a bridge: we take something familiar—a lantern, a storm, a path—and we use it to illuminate something unfamiliar. We do this not because we’re foolish, but because our minds need something solid to stand on before they can reach for the unknown.

Metaphors give us a bit of light, the way a small candle chases back a dark room. They don’t show everything—just enough to help us take the next step, enough to keep us from stumbling.

And in a world full of uncertainty, that little bit of light feels like a blessing.

When life grows heavy or confusing, metaphors do quiet emotional work in the background. They soothe nerves. They soften fear. They give us a story to hold when reality feels like too much to carry bare-handed. In that sense, metaphors are like gentle medicine: they take the edge off our worry, restore a little meaning, help us get through the night.

They offer comfort when facts alone cannot.

When people feel powerless, metaphors provide a sense of understanding—sometimes only a sliver, but a sliver is enough to feel human again. A familiar image can make us feel steadier, as though we’ve regained some small measure of control in a world that often feels uncontrollable. That feeling—of grasping the shape of something—is deeply attractive, especially in times when society feels frayed or broken.

The truth is simple:

metaphors don’t spread because they’re perfect; they spread because they give us emotional shelter.

Life can be confusing—war, rising prices, lost jobs, disappointments, political failures. These experiences stir up all the ancient emotions in us: fear, shame, bewilderment, helplessness. And when the world becomes this tangled, our hearts look for a story that feels manageable.

A metaphor offers exactly that.

A neat cause.

A clean picture.

A sense of who’s responsible.

A tale that feels true even when the details are fuzzy.

Real explanations—economic chains, political decay, historical accidents—are messy and unsatisfying. They require patience. They give no quick comfort.

But metaphors?

Metaphors lend us the warm illusion of clarity.

They are the stories we reach for when the real story is too complex, too painful, or simply too heavy for a tired mind at the end of a long day.

And so, in every society and every century, metaphors become companions to the human spirit—not just because they help us think, but because they help us feel.

Summary

Language helps us organize complexity; metaphors extend that function by mapping the unknown onto the known.

Metaphors offer partial clarity and emotional containment, giving shape to experiences that are otherwise overwhelming.

They endure because they simplify confusion into graspable form, providing both cognitive structure and psychological relief.

The Bounds and Burdens of Metaphors

For all their usefulness, metaphors have limits of their own. A metaphor is like a walking stick—it helps you steady yourself, but it cannot tell you where the road bends. If we lean on it too heavily, it breaks; if we forget that it is only a stick, we mistake it for the path itself.

And if you noticed that I used a metaphor to explain a metaphor, you’re right. These things have a way of slipping into our sentences the way old friends slip into a room—quietly, and before we quite realize it.

Every metaphor means something slightly different to every person who hears it. Words are only symbols—little marks on a page that stand in for much larger ideas. And because each of us carries different memories, fears, and hopes, we project our inner worlds onto those symbols. The same phrase that comforts one person may alarm another. The same image that clarifies things for one reader may confuse the next.

That is simply the nature of language. Words, after all, are only tools—simple instruments we use to make sense of a world far larger than ourselves.

But here’s the danger:

when metaphors become shorthand for truth, they can stop us from thinking deeply.

A metaphor does not grow and change just because the world has. It can remain frozen even while circumstances shift around it. And if a society continues to use an old metaphor in a new situation, the gap between the image and the reality eventually widens. Meaning begins to leak out. The metaphor stretches… expands… and finally becomes so vague that it can be twisted to mean almost anything—or nothing at all.

In fragile or broken societies, this problem becomes even sharper.

Metaphors spread quickly because they offer:

simple answers to complicated problems,

comfort when people feel powerless,

a sense of belonging when community is fraying,

and the warm illusion of control in a world that feels unsteady.

But in the wrong hands, they also become tools of division.

Leaders can wield them like weapons—drawing lines between “those who understand” and “those who don’t,” between the loyal and the disloyal, between the enlightened and the outsiders. Big metaphors, wrapped in big words, can create distance between a representative and the people they claim to represent. It becomes a kind of performance: superiority disguised as wisdom.

History shows us that in times of collapse or fear, this pattern repeats.

Authoritarian leaders—of every era—have relied on sweeping metaphors and conspiratorial images to:

rally supporters,

assign blame,

silence critics,

justify harsh actions,

and distract from their own failures.

When societies feel unsteady, metaphors stop illuminating and begin hardening. Leaders reach for images that sound simple, decisive, and urgent—and suddenly a symbol becomes a tool of control. In such moments, metaphor becomes a political instrument, not a lantern of understanding. And the consequences can be enormous.

Examples of Historical Metaphors Used for Control, Fear, and Justification

• “The Body Politic” — used since ancient Greece and Rome

Rulers cast society as a single body with the king as the “head.”

Anyone who questioned authority became a “diseased limb.”

Rebellions were framed as “infections” requiring “amputation.”

• “The Ship of State” — Plato to early modern Europe

Leaders warned that without obedience to the captain, the “ship” would capsize.

This metaphor often justified suppressing dissent, since mutiny = destruction.

• “Pests” or “Vermin” — used by authoritarian regimes throughout the 20th century

Opponents were dehumanized as “rats,” “insects,” “parasites,” or “infestations.”

Once you cast a group as a plague, extreme measures suddenly appear “necessary.”

• “The Fifth Column” — Spain (1930s), then globally

A supposed secret enemy “within” the population.

Leaders used this image to purge critics, justify surveillance, and demand loyalty.

• “The Enemy Within” — McCarthyism, Cold War politics

A metaphor that turned ordinary neighbors into potential traitors.

Suspicion itself became a political weapon.

• “National Purification” — early 20th-century fascist movements

The nation was portrayed as a body that needed “cleansing.”

Mass repression was framed as hygiene.

• “Storms” and “Floods” — used by emperors, czars, and modern strongmen

Economic or political crises were depicted as natural disasters.

Leaders claimed only they could “hold back the flood,” discouraging alternatives.

• “The Iron Curtain”

A Cold War metaphor that created a psychological wall long before any borders were set.It cast the world into an us-versus-them frame with no shades of gray.

• “The Motherland / Fatherland”

Leaders cast themselves as protectors of the “parent” nation.

Calls for sacrifice become moral obligations—who refuses to defend their mother?

• “The Racial Hierarchy as a Ladder”

White supremacist systems framed society as a natural ladder.

“Moving up” meant accepting the ladder; questioning it meant disrupting “order.”

“The Nation as a Family”

Leaders cast citizens as “children” and themselves as the “father” or “guardian.”

Dissent becomes childish disobedience; obedience becomes maturity.

Summary

Metaphors help us navigate complexity, but they are partial tools; when mistaken for literal truth, they restrict thought and obscure changing realities.

Because individuals project their own histories and emotions onto symbolic language, metaphors become unstable and easily stretched, especially in moments of social strain.

In fragile societies, leaders can weaponize metaphors—using simple images to assign blame, divide communities, and justify coercion—turning language from a tool of understanding into a tool of control.

Footer Navigation:

👉 Next in the series: Part 2: Case Study: History of the Invisible Hand → (Links coming soon)

👉 Back to intro: The Ethics of Economic Metaphors — Welcome → (Links coming soon)

🌿 Series Navigation

Read all parts: [Links coming soon]

Start from Part 1: [Links coming soon]

Next post: [Links coming soon]

Previous post: [Links coming soon]