The Ethics of Economic Metaphors: What Do We Do Next? (Individual Level) Part 8

How each of us can ask better questions, demand clarity, and think more gently about public ideas.

Series Note:

👉 This post is Part 8: What Do We Do Next? (Individual Level) for my 9-part series The Ethics of Economic Metaphors.

You can read all parts here → (link coming soon)

How Good Ideas Get Misunderstood

Let me begin gently—like an old friend settling into the porch swing beside you. All of us, even the wisest elders, carry limits in how we think. We don’t see every angle, we don’t remember every detail, and the world often races faster than our understanding. Because of this, we lean on metaphors—little word-pictures that steady us when life feels confusing.

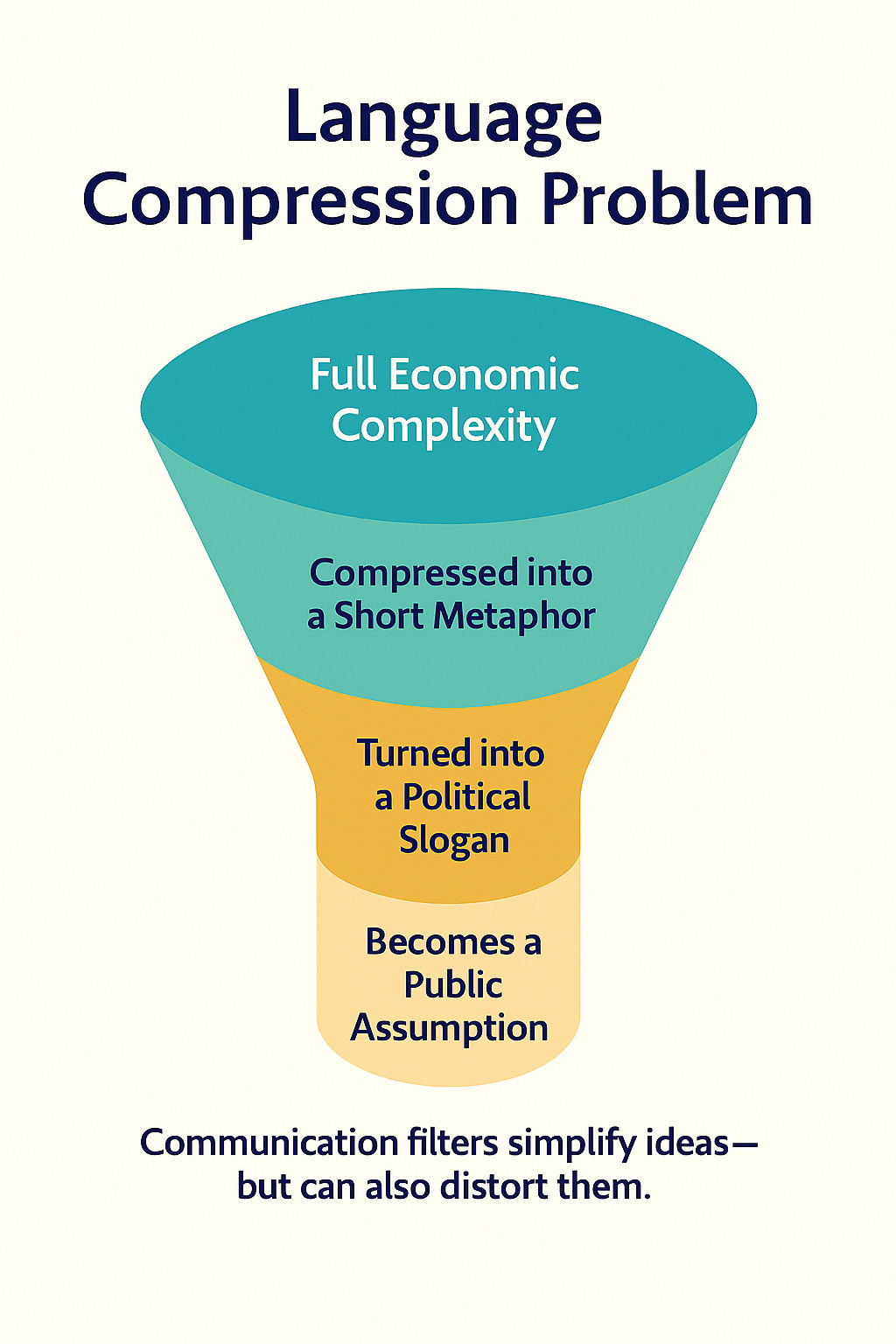

But metaphors, like stories passed around a family table, stretch over time. They grow, they wander, they pick up new meanings along the way. And when they stretch too far, they can stop guiding us and begin misleading us—especially when we forget that they show only a slice of the truth, never the whole loaf.

Where the Invisible Hand Slipped

A good example is the old phrase “the invisible hand.” Many leaders speak of it as though it were a law of nature—something as dependable as the sunrise. But they rarely pause to explain its limits. When the invisible hand is described as something that always brings harmony, folks are given a picture that simply isn’t accurate.

This isn’t about being for or against markets; it’s about being honest. If a policymaker treats the invisible hand as unfailing, they leave the public with a false map of how the world works. Markets don’t fix every problem. People make mistakes. Companies sometimes cause harm. And leaders, with the best of intentions, can promise a safety that isn’t really there.

Sometimes policymakers misunderstand the metaphor themselves. Other times they use it because simple stories are comforting and easy to repeat. But whatever the reason, the public ends up holding a picture that’s missing too many pieces.

The invisible hand began as one small idea in one small corner of Adam Smith’s work. Over time, it grew into a towering symbol used to argue that markets should always be left alone. But neither Smith nor modern thinkers—especially those who study human error—believed the metaphor worked everywhere.

And that is where the ethical problem lies. When a metaphor is treated as perfect, people are left with half-truths. In moments of crisis—such as in 2008—this misunderstanding encouraged too much trust, too little caution, and a dangerous blindness to what was happening beneath the surface.

The Humble Duties of Public Life

Good leaders—like good parents, good teachers, and good elders—remember two simple truths: people have thinking limits, and metaphors have meaning limits. None of us sees the whole world at once, so we lean on word-pictures to guide us. But leaders must never forget that those pictures have boundaries.

That is why leaders carry a moral duty to speak plainly, explain themselves kindly, and resist leaning too hard on old sayings just because they sound wise. Clarity, offered with warmth, is one of the finest gifts a leader can give.

A thoughtful leader should:

understand the words they use,

know where those words come from,

define their metaphors plainly,

never assume everyone shares the same meaning,

and trust the public to understand complexity when it’s explained with care.

Honesty isn’t a burden in public life—it is the very ground beneath it.

A Gentle Hand on the Wheel

Picture a winding road. We still need painted lines, cautious speed limits, and a touch of shared discipline. If every driver rushed ahead thinking only of themselves, the consequences would be quick and painful. Markets are much the same. Wise government doesn’t control the road; it simply keeps it safe. Too many guardrails, and nothing moves. Too few, and people get hurt.

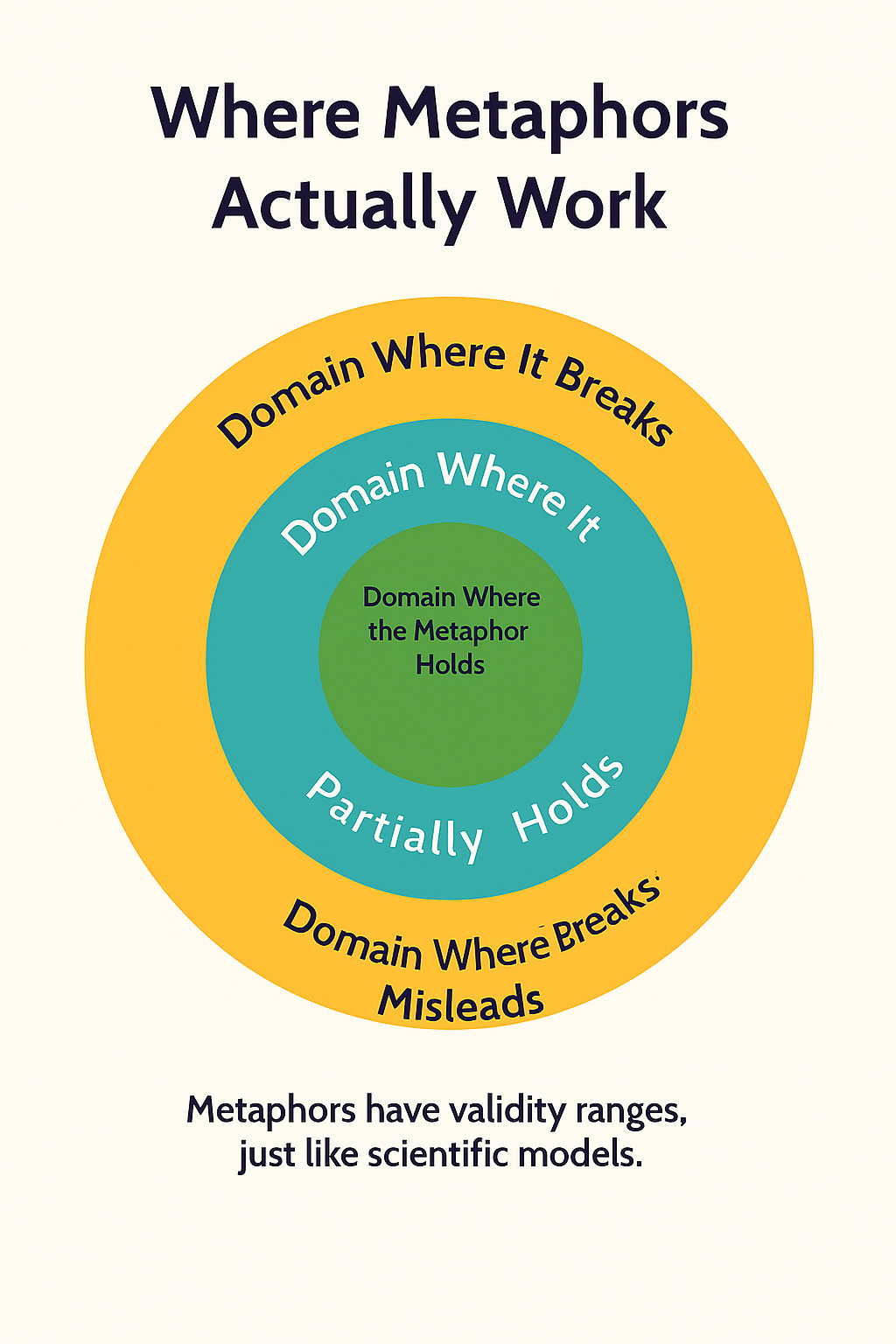

Part of that stewardship is tending to the metaphors we use. A careful leader explains where a metaphor begins and where it ends, so no one mistakes a figure of speech for the whole truth. Leaving people to guess at those limits is a quiet form of paternalism—one that treats citizens as incapable of understanding the full picture.

John Stuart Mill reminded us that people choose well when given full information. It is not a leader’s place to decide what citizens can “handle.” Their job is to share what they know—and to go learn what they do not know.

If a leader discovers they have used a metaphor incorrectly, the honorable path is simple: acknowledge it. Words do evolve, but when those words guide public decisions, leaders must name that evolution openly. And if someone cannot explain the metaphors guiding their decisions, perhaps they are not ready to steer matters of economy, defense, or public safety.

As citizens in a democracy, we should be able to ask our leaders how they are using those words—and trust that they know how to use them wisely. In a free society, we are not meant to simply accept metaphors as magic answers. And democracy cannot survive on wrong models. It needs honesty.

This is where we, the people, have a responsibility too. We must ask questions. So we should feel comfortable asking them:

“What do you mean?

Where does this idea work, and where does it stop working?”

The Ethical Responsibility

In a democracy, citizens cannot make informed decisions if policymakers promote ideas like the “invisible hand” without revealing where that metaphor breaks down.

Real people operate with bounded rationality—limited attention, emotional bias, and imperfect heuristics. humans have limited information, limited attention, and limited foresight. If policymakers fail to disclose the limits of their economic ideas, they are not merely simplifying; they are withholding material facts. In a democracy, that crosses from rhetoric into ethical failure, because citizens cannot consent to policy based on a metaphor whose boundaries are never explained

A Gentle Word About Honest Speech

When a metaphor changes, and a leader knows it, they owe the public a plain, humble explanation. It isn’t right to lean on old phrases as though they still carry their former meaning, nor to borrow a famous name to make an argument seem stronger than it is. In a healthy society, truth must stand on its own two feet—metaphor or no metaphor, reputation or no reputation. Words deserve care, courage, and responsibility. That is how trust quietly grows.

Key Points

Leaders must explain things clearly. They shouldn’t use confusing sayings or old phrases without telling people what they really mean.

Rules and guidance matter. Just like roads need signs and lines, societies need gentle rules so people stay safe and make good choices.

Honesty builds trust. Leaders should tell the truth about where ideas work and where they don’t, so citizens can make fair and informed decisions.

Individual understanding matters—but systems shape us too. Let’s widen the lens and look at the structures around us in Part 9.

👉 Next in the series: What Do We Do Next? (System-Level Solutions) Part 9→ (link coming soon)

👉 Back to How Economic Metaphors Guide Us (and Sometimes Mislead Us (Part 7)

→ (link coming soon)

🌿 Series Navigation

Read all parts: (link coming soon)

Start from Part 1: (link coming soon)

Next post: (link coming soon)

Previous post: (link coming soon)