The Ethics of Economic Metaphors: The Crash and Costs of Blind Faith (Part 6)

What happens when policymakers trust a metaphor more than the people it affects.

Series Note:

👉 This post is Part 6: The Crash and Costs of Blind Faith for my 9-part series The Ethics of Economic Metaphors.

You can read all parts here → (link coming soon)

The Invisible Hand Slipped

In 2008, the invisible hand slipped. Mortgage-backed securities—those brilliant inventions of financial alchemy—began to rot from within. What had seemed like order turned out to be a pyramid of borrowed faith. The fall was swift and merciless.

Families lost their homes. Retirees watched lifelong savings vanish in a week. Once-busy factories fell silent; office lights flickered out. The invisible hand that was supposed to guide prosperity now seemed to push millions into ruin.

From business school to Wall Street’s towers, a metaphor had grown into a movement—and ended as a warning in the 2008 Great Recession. When the dust finally settled, the cause of the Great Recession wasn’t mysterious at all—it was the same old story wearing a new suit.

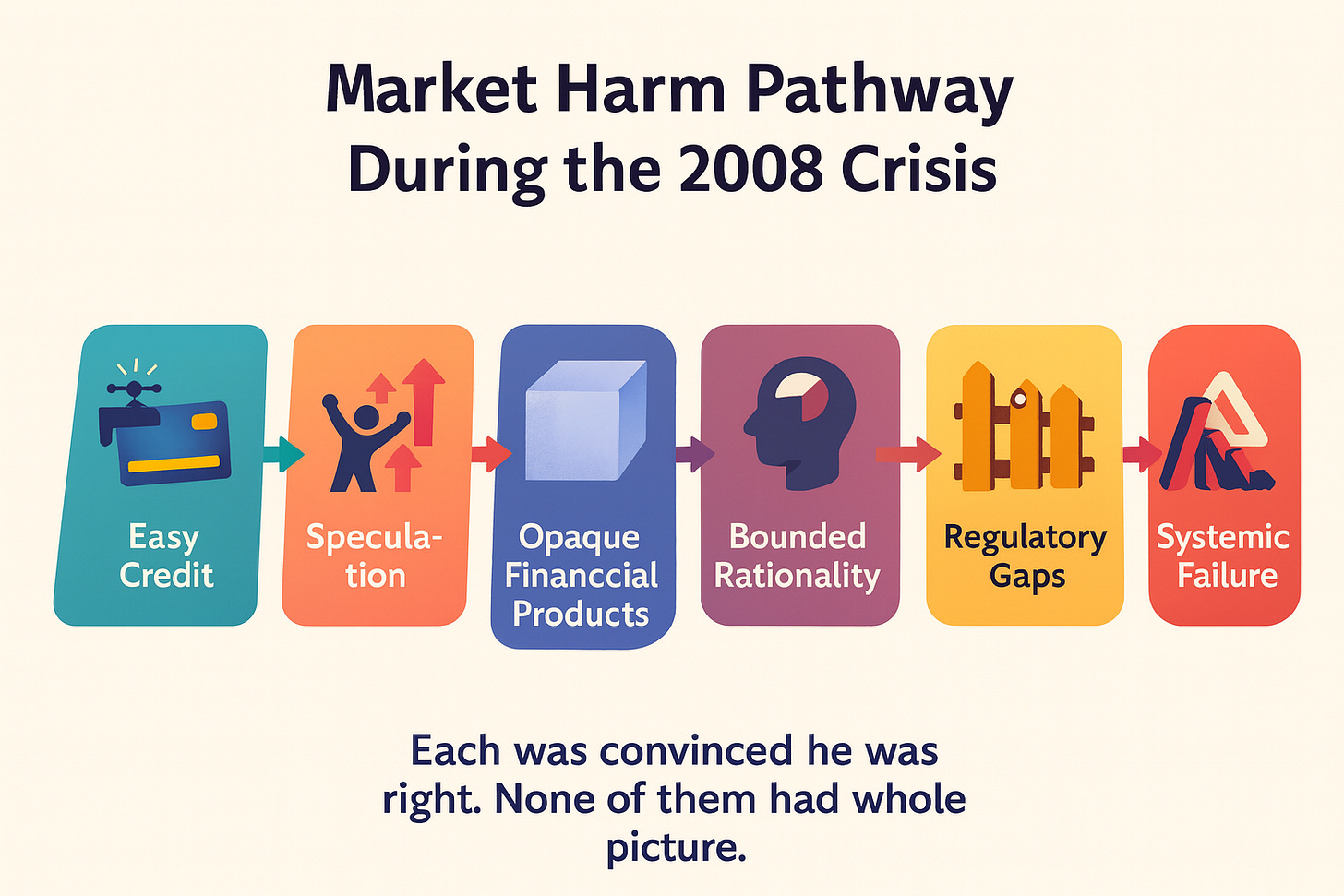

At its core, the financial crisis had three familiar villains:

1. Excessive risk-taking by banks and financial institutions—especially through subprime mortgages sold as “safe” investments.

2. The Bubble That Everyone Blew: Easy credit and feverish speculation sent housing prices soaring far beyond reason.

3. Faith Without a Safety Net: Regulators and investors alike trusted that markets could police themselves—that the “invisible hand” would swoop in before things got bad.

But it didn’t. The crash showed that when belief hardens into dogma, even the smartest systems can collapse—and that the invisible hand, when left entirely alone, sometimes lets go.

The Cost of Blind Faith

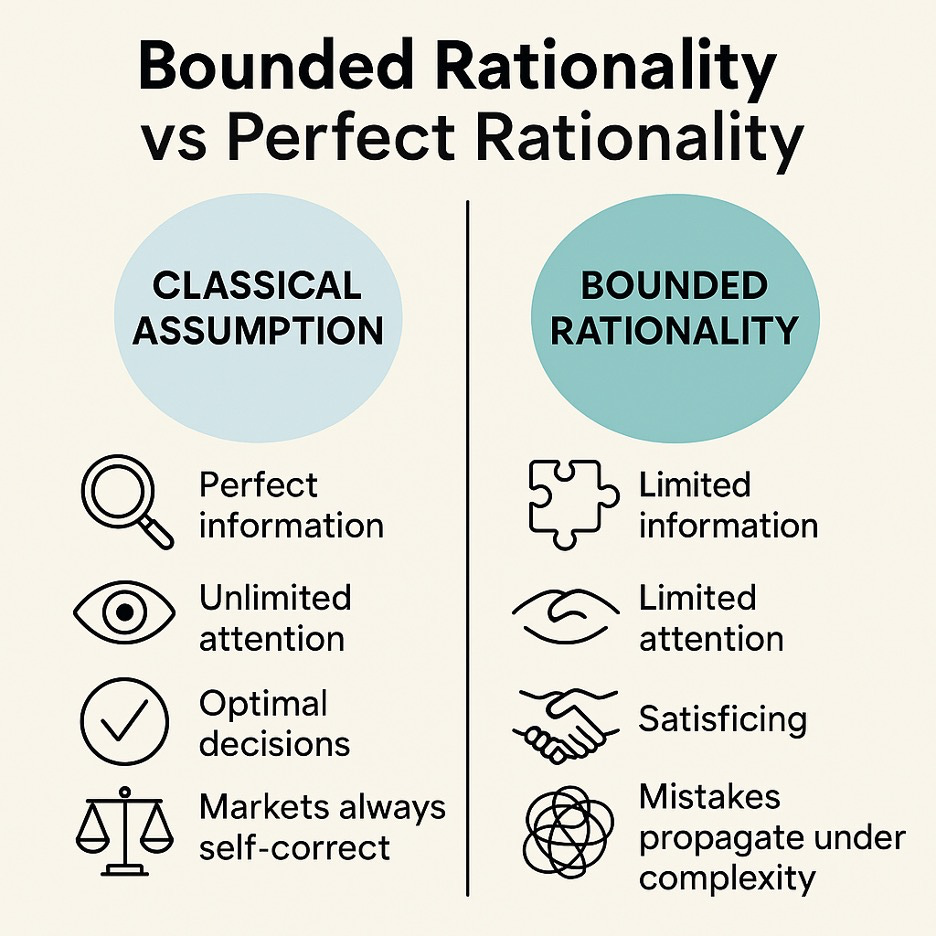

Looking back, the 2008 financial crisis was a hard lesson in misplaced faith. For decades, we’d trusted that markets could steady themselves—that the “invisible hand” would always correct excess, reward prudence, and punish risk. But when the crash came, it showed just how fragile that belief really was.

The meltdown revealed the limits of blind confidence in metaphors, especially one that simplify the complexity of the the market’s natural balance—and reminded the world that even the most trusted systems, headed by very smart people can stumble without deep thought, oversight, and moral grounding.

Some even treated the “invisible hand” as a stand-in for the market itself—the quiet, almost mystical force said to guide resources to their best use (Grampp 441–462).

But here’s the irony: the market is a metaphor too. So we ended up with one metaphor propping up another, like two mirrors reflecting the same illusion.

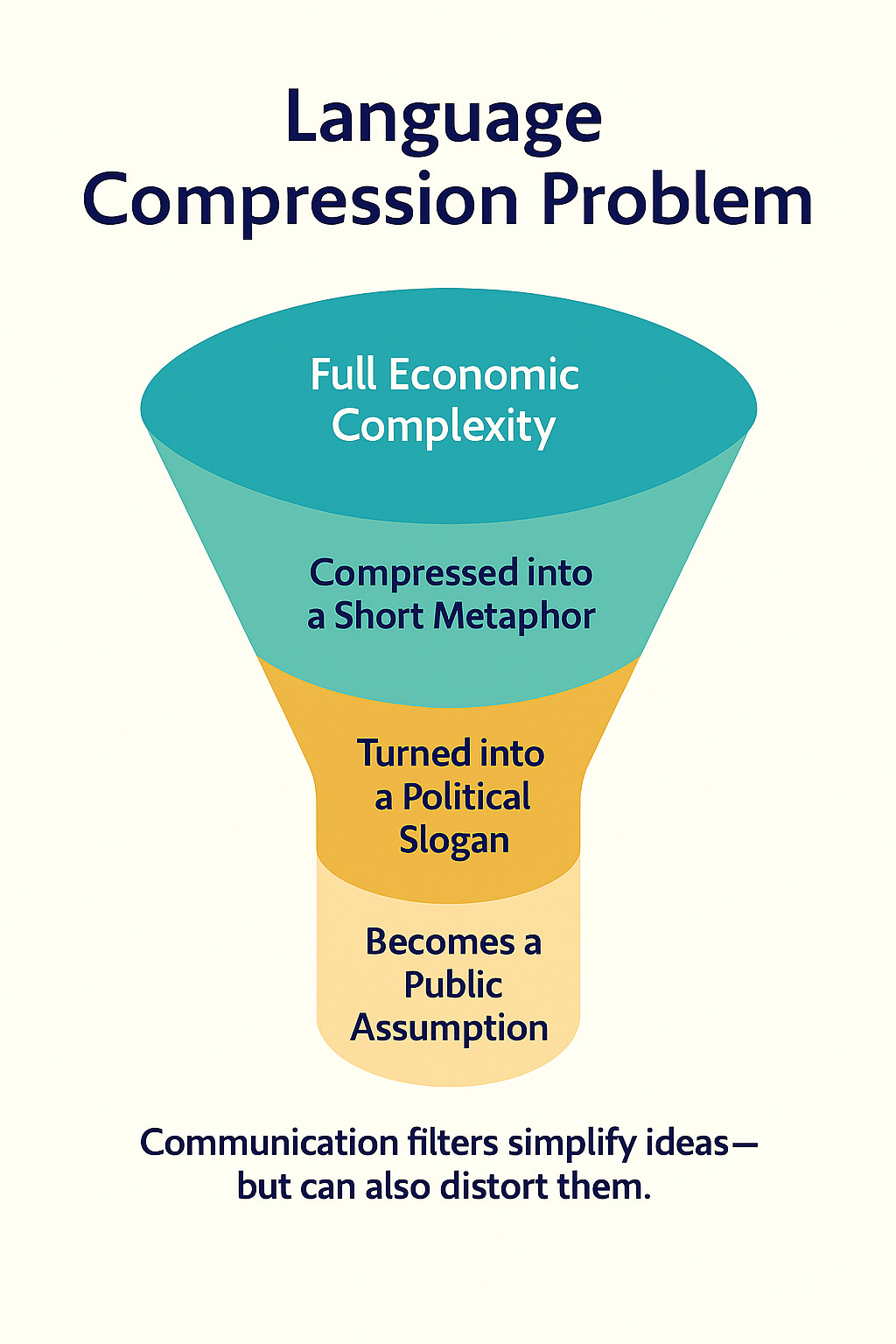

And perhaps most striking of all, it showed that words have power—that a simple metaphor, repeated often enough, can shape entire economies and steer the course of nations. What started as a gentle metaphor for human behavior become an article of faith—proof that a few well-chosen words can move not just markets, but minds.

Somewhere along the way, Adam Smith’s modest image of an “invisible hand” metastasized into a cultural myth beyond his intended meaning.

Key Points

The 2008 financial crisis revealed the limits of treating the “invisible hand” as a self-correcting mechanism; excessive risk-taking, speculative bubbles, and regulatory complacency exposed the gap between market ideology and actual institutional behavior.

The crisis demonstrated that reliance on a metaphor—one that overstated market stability and understated human cognitive and institutional constraints—contributed to policy choices that failed to provide necessary oversight or safeguards.

The collapse underscored that markets are human systems, vulnerable to error and distortion; Smith’s original caution about unchecked self-interest and the need for prudent regulation was ignored, allowing the metaphor to evolve into a comforting myth rather than a bounded analytical insight.

Why did the Metaphor Miss the Mark?

Adam Smith understood something simple and very human: people don’t always know what is truly good for them. He warned that self-interest can “miss the mark.” As he wrote, people often misjudge what will make them happy—or they chase quick pleasures that lead them into trouble later (WN, Book I, Ch. 6; Grampp, 444).

Even very smart people sometimes choose short-term comfort instead of long-term well-being.

So yes, it’s true:

We don’t always act in our own best interest.

This isn’t meant to be anti-market. It’s simply an honest reminder.

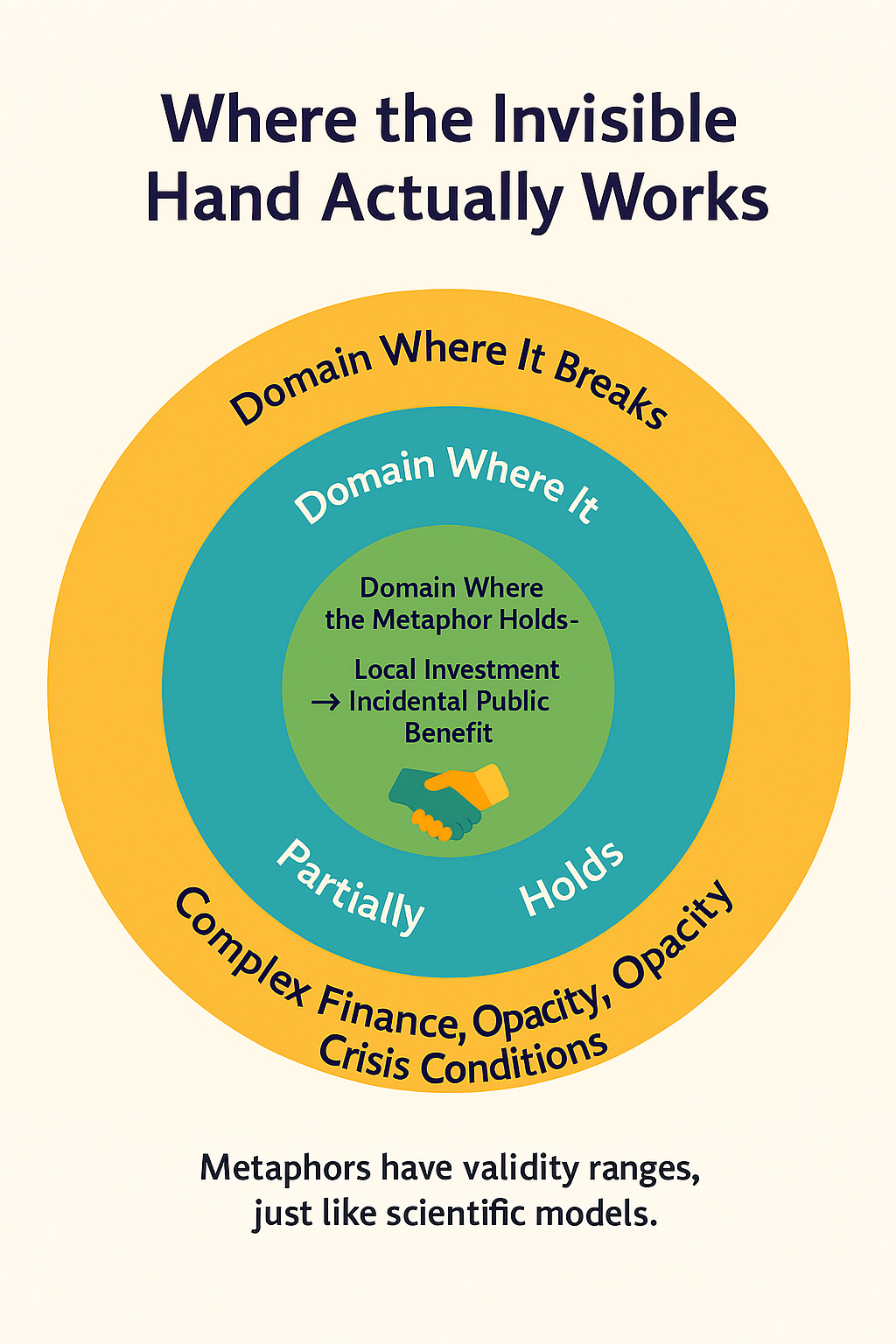

The “invisible hand” can work, but only inside the small space where it truly applies. Step outside that space, and the idea becomes more of a comforting story than a guiding truth.

As we talked about earlier, Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” wasn’t a grand rule of the universe. It was just a quiet observation about one kind of merchant. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith mentioned it only once. He was describing a merchant who preferred to invest close to home—not because he loved his country, but because he felt safer that way. By keeping his money local, he accidentally helped the local economy grow by creating jobs and movement.

And that’s really all Smith meant.

He never said everyone’s self-interest magically helps society.

He never said governments should step aside completely.

His point was gentle and realistic:

Sometimes, private choices can help the public good—but not always.

For as we discussed in early parts, Adam smith was a proponent of government oversight. He saw clearly the danger in unleashing ambition without guardrails. He worried about merchants who manipulated laws, cornered markets, or misled the public for profit.

Smith’s caution is unmistakably firm:

“The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce

which comes from this order [those who live by profit]

ought always to be listened to with great precaution.”

— Book I, Chapter 4

What began as a small, careful observation by smith became a twisted—a kind of spell used to quiet doubts about markets and shrink the role of government. It painted economies as smooth, self-correcting machines instead of what they really are: human systems—messy, emotional, and full of mistakes.

Smith, the moral philosopher, would likely have raised an eyebrow.

He knew words could build nations—or blind them. Whether a metaphor reveals truth or hides it depends on who’s speaking, and for whose benefit. And the most powerful interpretations often come from the top—from economists whispering in government halls, financiers steering policy, and media voices repeating the same reassuring tale until it starts to sound like truth.

Part of why the metaphor spread is because it feels soothing.

It tells people, “Don’t worry—the system will take care of itself.”

Over time, the phrase stretched far beyond what Smith intended.

It became a kind of shield—something people used to avoid hard questions.

Sometimes politicians and even some economists used it to skip explaining their ideas deeply. Corporations used it to say they were doing good simply because they were being efficient. Policymakers used it to justify doing nothing, as if “the market” were a moral force all on its own.

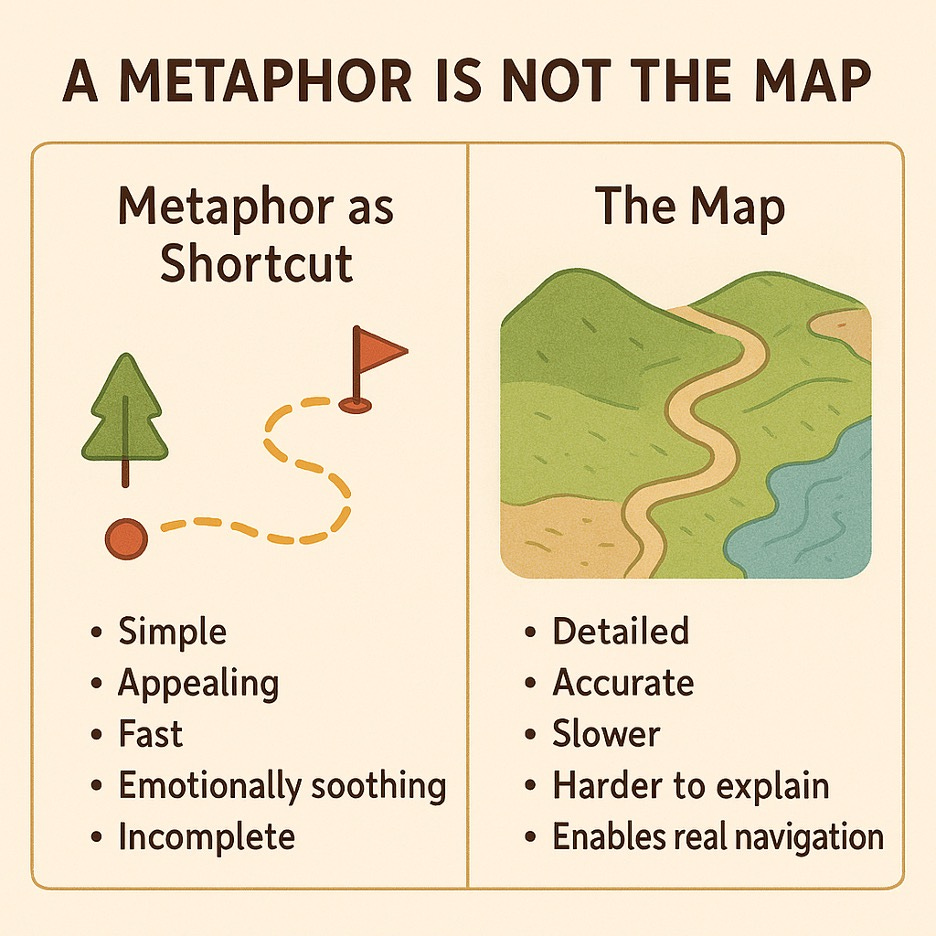

But when one metaphor starts meaning many different things to many different people, it stops giving us clarity.

Eventually, it becomes like a word worn smooth from too much use—so soft and stretched that it loses its meaning altogether.

And so, gently, we come back to Smith’s original wisdom:

Words can guide us, but only if we remember what they really meant in the first place.

Let me be clear: I’m not saying the “invisible hand” caused the Great Recession. A single metaphor can’t do something that big. But the way people used it—carelessly, as a shortcut for certainty—was a small sign that our thinking was getting a little thin. When leaders quoted Adam Smith, a man from a very different time, as if he had all the answers for today, it was like seeing the oil light blink on in a car. Not the cause of the problem, but a gentle warning that something needed attention.

With that said, here are a few quiet truths worth holding:

The metaphor may have shaped our mindset, making certain ideas feel safe.

It sometimes let us skip careful thinking.

It encouraged a soft sort of faith, as if an unseen force would fix things.

It suggested that markets always fix themselves, even when they don’t.

And it softened our reasoning at a moment when clarity was needed.

If the meaning had stayed close to Adam Smith’s original idea, perhaps the damage would have been smaller.

My warning is humble: when our words become too quick and too sure, trouble may be quietly forming beneath them.

In part 7, we gather what the financial crisis taught us about words—and their limits.

Key Points

People don’t always make the best choices, so the “invisible hand” doesn’t always work the way some leaders claim.

Adam Smith only meant the idea for small situations, not for every part of the economy—so using it as a “magic rule” can cause confusion.

When people used the metaphor too loosely, it made some leaders over-trust markets and ignore warning signs, which helped mistakes grow during big events like the 2008 crash.

Footer Navigation:

👉 Next in the series: How Economic Metaphors Guide Us (and Sometimes Mislead Us (Part 7) → (link coming soon)

👉 Back to When the Metaphor Took Over The Marketplace (Part 5)

→ (link coming soon)

🌿 Series Navigation

Read all parts: (link coming soon)

Start from Part 1: (link coming soon)

Next post: (link coming soon)

Previous post: (link coming soon)