The Ethics of Economic Metaphors: A Recap of How Economic Metaphors Guide Us (and Sometimes Mislead Us) Part 7

How economic metaphors shape understanding—and how they mislead when stretched beyond their purpose.

Series Note:

👉 This post is Part 7: A Recap of How Economic Metaphors Guide Us (and Sometimes Mislead Us for my 9-part series The Ethics of Economic Metaphors.

You can read all parts here → (link coming soon)

A recap: Let me gather the thoughts we’ve walked through, like picking up smooth stones along a riverbank.

First, metaphors don’t stay the same forever. They slowly change meaning as people use them. Sometimes we don’t even notice the shift happening.

In economics, words and metaphors are used to explain ideas. But over time, a metaphor can stretch too far. It can start to mean things it was never meant to mean, and sometimes it ends up helping the wrong arguments.

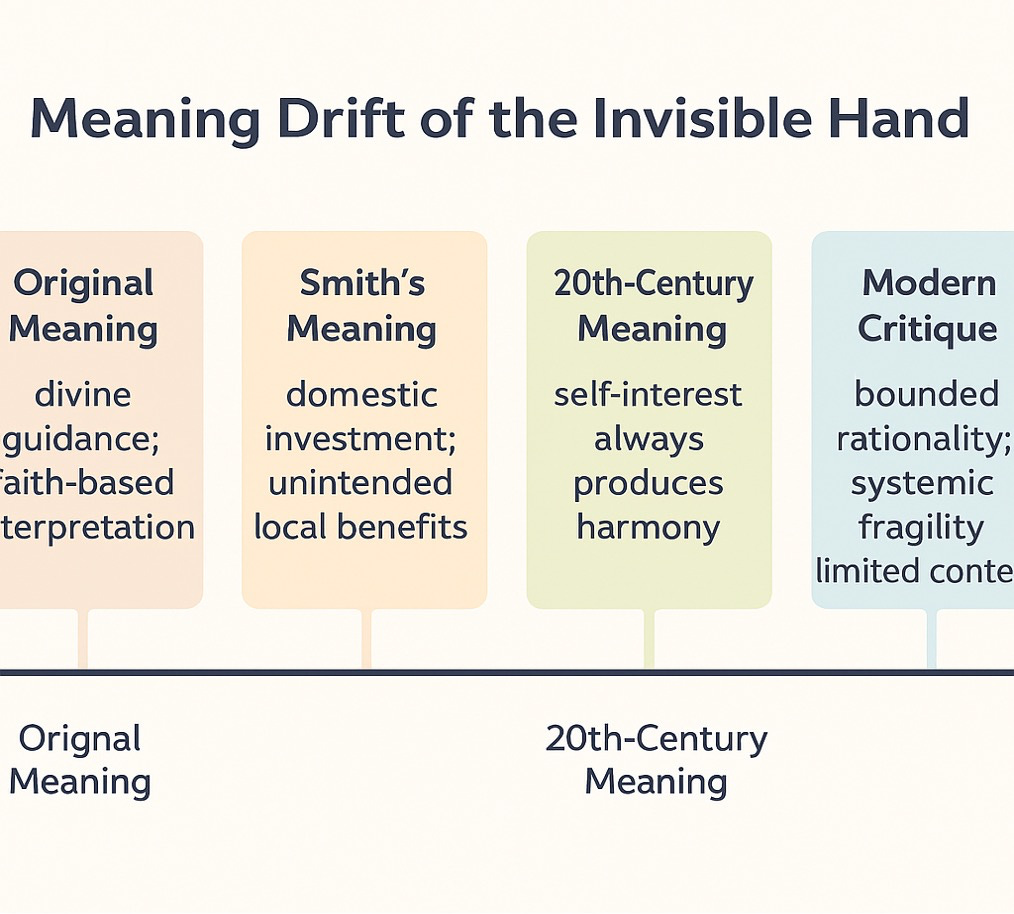

Adam Smith never treated the “invisible hand” like a big, shining idea. In truth, he mentioned it only once in The Wealth of Nations, almost like a quiet footstep. That tells us it wasn’t the heart of his thinking. Many smart people of his time didn’t pay attention to it at all. Economists like Thomas Malthus (1798), David Ricardo (1817), and J.S. Mill (1849) never even wrote about it (Kennedy 240).

It wasn’t until many years later—around the middle of the 1900s—that the phrase became famous. By then, people who admired Smith had turned this small metaphor into a big symbol, almost a kind of cheer: a sign of trust in the market’s “invisible wisdom.” The gentle surprise is this: Smith’s later fans became much more excited about the “invisible hand” than he ever was.

As time passed, new meanings kept sticking to the phrase. Some people began saying it meant “laissez-faire,” or the idea that the market works best when no one interferes. This gave business leaders and government officials a comforting story: that if we leave markets alone, “every deal” and “every profit” would fit neatly into a perfect, self-correcting system.

The economist Milton Friedman once said the market offered “the possibility of cooperation without coercion.”

But like a soft piece of clay, the word kept stretching. It grew beyond what Smith meant.

First it meant faith.

Then it meant domestic growth.

Then unlimited self-interest.

Then anti-government ideas.

And today, people—myself included—are gently asking: What are its true limits now? Should we celebrate it? Question it? Or simply understand it more clearly?

You see, this is what metaphors do.

They grow and stretch and wander.

And if we’re not careful, they grow so wide that they stop meaning much at all.

Like a wise old friend might say:

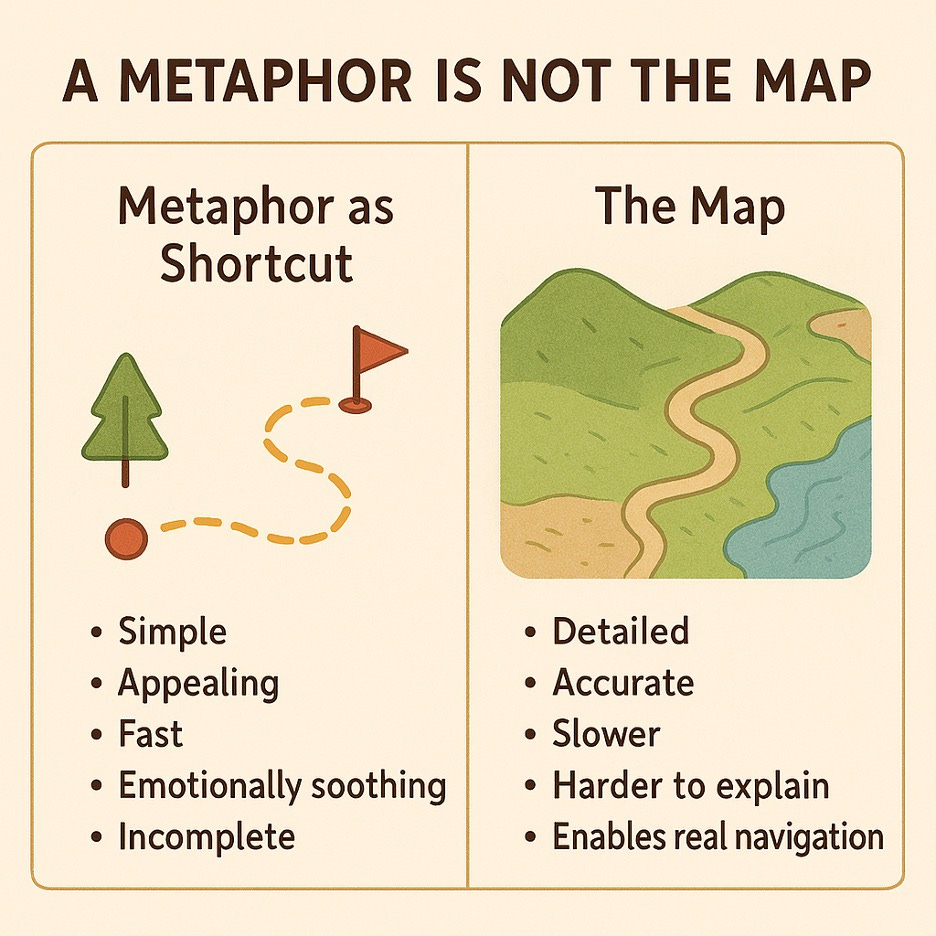

“A metaphor is a wonderful lantern—but it can only light the part of the path it was built for.”

Second, words are really just tools—little symbols we draw on a page to stand in for bigger ideas. The point here isn’t to blame anyone, not teachers, not leaders, not politicians. It’s simply to say that every system humans make will have limits, because we have limits. Imperfect people can’t build perfect things, no matter how hard we try.

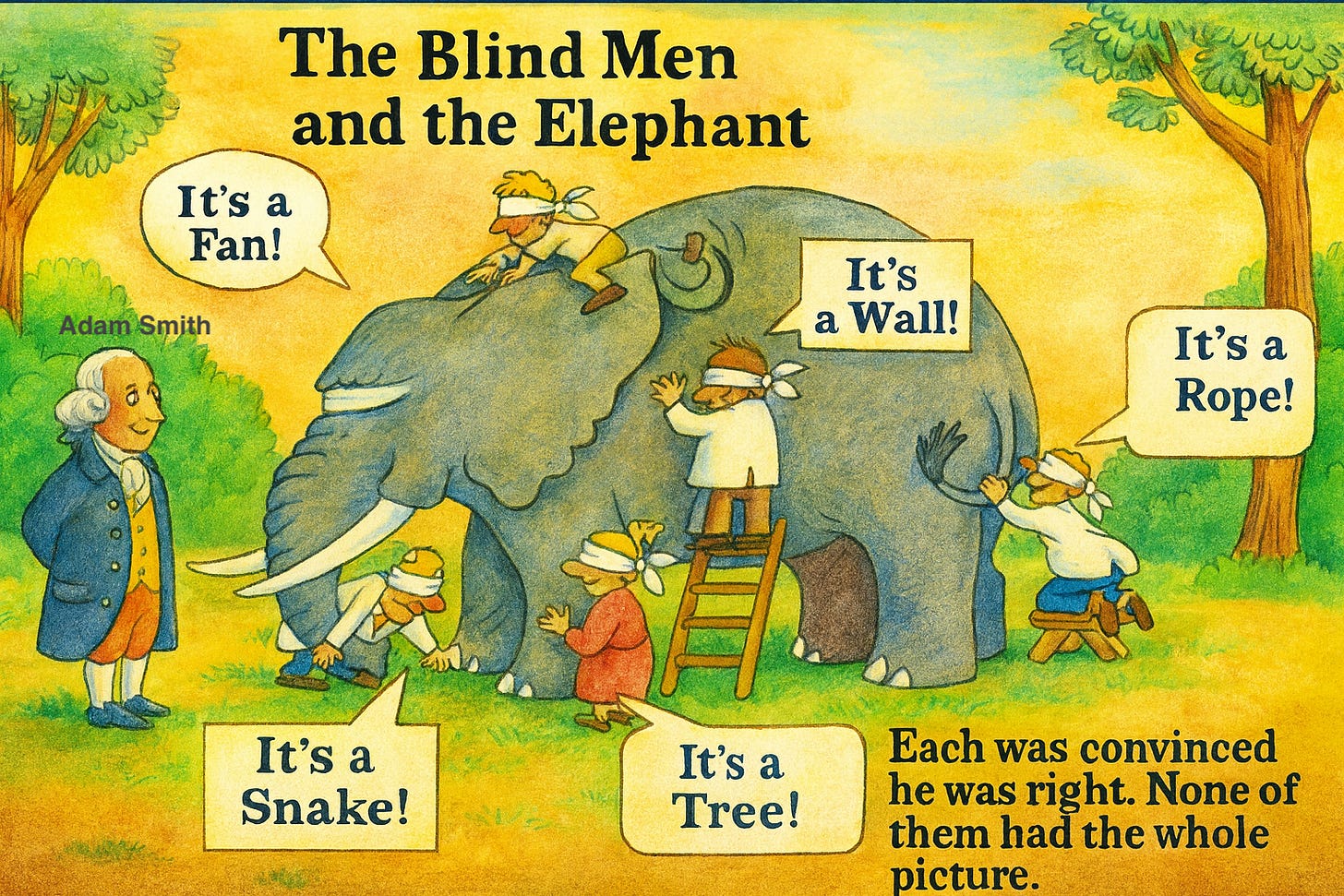

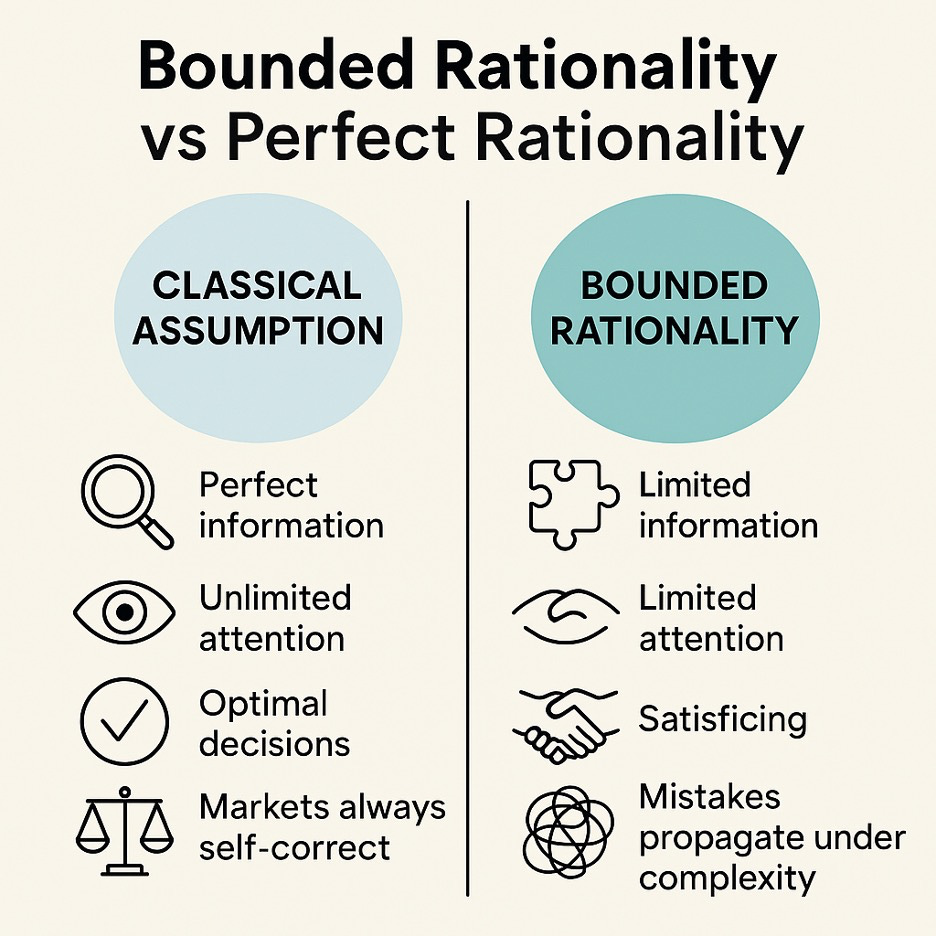

Classical economic vision of the “invisible hand” rests on a false assumption: that humans are perfectly rational calculators who optimize every decision. In reality, people operate under bounded rationality — limited attention, incomplete information, time constraints, cognitive shortcuts. Markets are therefore not composed of omniscient agents whose free choices automatically create optimal outcomes. They are composed of humans with narrow bandwidth, relying on habits, imitation, satisficing, and institutional routines. In this view, the invisible hand is less a universal force of optimization and more a metaphor for how decentralized behavior sometimes—but not always—produces coherence.

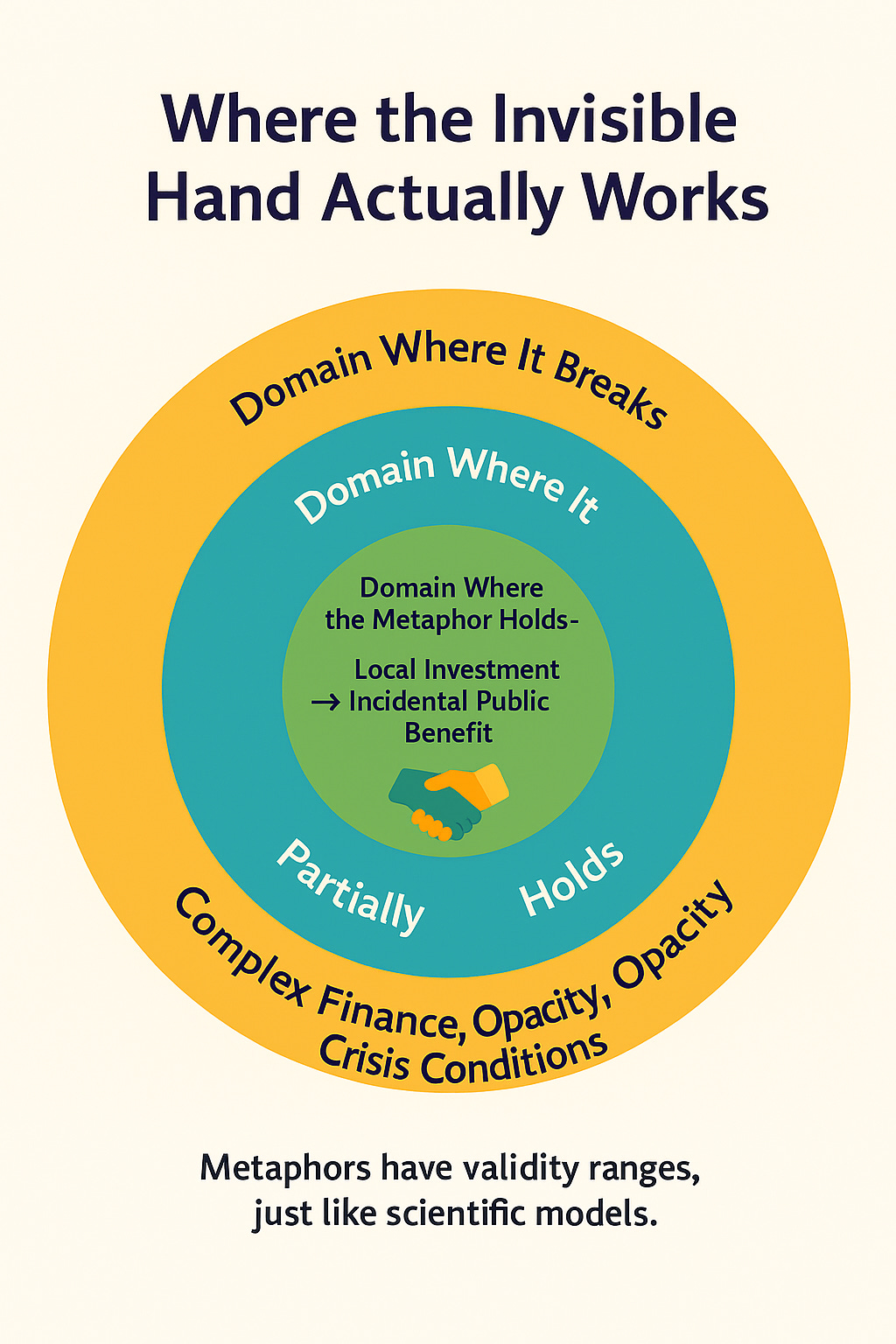

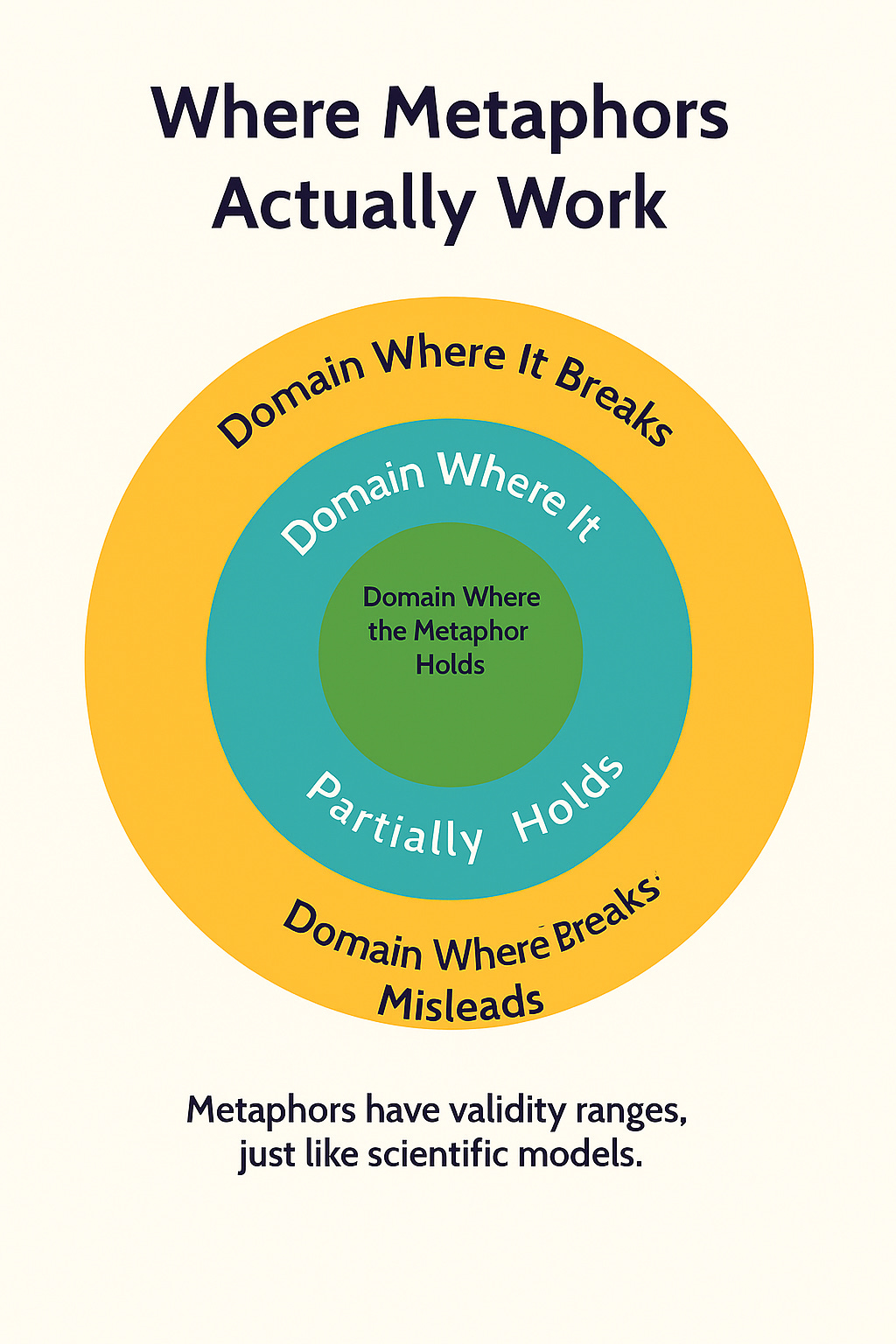

Third, metaphors have boundaries—just like a map only shows a certain area. If we pretend a metaphor explains everything, we end up confused, and sometimes people get hurt by decisions made on the wrong idea.

Because real people face cognitive limits, economics must be rebuilt on models of actual human behavior, not abstract perfection.

When markets become complex, opaque, or emotionally charged—as during the 2008 financial crisis—bounded rational decisions can cascade into systemic failures. Not because individuals are irrational, but because they are human, operating with imperfect heuristics inside unstable institutions. Economics should not be a theology of the market; it should be an empirical science of decision-making.

The invisible hand works only under conditions where human cognitive limits are aligned with institutional structure. When those limits are exceeded, markets do not self-correct—they amplify errors. In that sense, let’s follow Smith’s ideas: the market can coordinate behavior, but only within the limits of human cognition.

So, I hope I’ve shown this gently:

Words can guide us, but only if we remember what they truly stand for. And when we stay honest about their limits, we find our way a little more clearly, and a little more kindly.

Key Points

Metaphors change over time. The “invisible hand” started as a small idea, but people kept adding new meanings to it—some that Adam Smith never meant.

People aren’t perfect thinkers. We have limited attention and information, so markets don’t always work magically on their own; they depend on real human behavior.

Metaphors have limits. If we use them as if they explain everything, we can make mistakes—so we must remember what they truly mean and where they stop working.

Understanding is only the first step. Next, in Part 8 let’s consider what each of us can do in our own thinking and conversations.

Footer Navigation:

👉 Next in the series: What Do We Do Next? (Individual Level) (Part 8)→ (link coming soon)

👉 Back to The Crash and Costs of Blind Faith (Part 6)

→ (link coming soon)

🌿 Series Navigation

Read all parts: (link coming soon)

Start from Part 1: (link coming soon)

Next post: (link coming soon)

Previous post: (link coming soon)