The Ethics of Economic Metaphors: When the Metaphor Took Over The Marketplace (Part 5)

A Timeline of how the invisible hand moved from modest insight to marketplace crisis.

Series Note:

👉 This post is Part 5: When the Metaphor Took Over The Marketplace for my 9-part series The Ethics of Economic Metaphors.

You can read all parts here → (link coming soon)

A Gentle Recap of Smith’s Original Meaning

Before we go any farther, it may help to return, just for a moment, to the heart of our earlier discussion.

There is a simple truth—offered here with no scolding, only with clarity:

Adam Smith used the phrase “invisible hand” only once in The Wealth of Nations, and not at all in the way it is most often retold today. My intention is not to correct anyone, but to bring the idea back into focus, the way one might gently clean the dust from an old lantern.

Smith’s invisible hand was never meant as a rallying cry for blind faith in markets. It was a small, careful observation about merchants who preferred to invest close to home—where their efforts naturally strengthened their own community, and in time, the wider nation. It was loyalty at work, not license. A soft reminder that prosperity often begins by tending the soil beneath one’s own feet.

For Smith, the invisible hand can guide toward the common good only when self-interest is held within the frame of conscience, responsibility, and care for one’s community. That is the quiet heart of the idea.

The evidence for this original meaning can be summarized in one humble thought:

Self-interest contributes to the public good only when it grows inside the boundaries of justice, care, and moral responsibility.

However, during the mid-20th century, economists and policymakers expanded Smith’s limited metaphor into a sweeping doctrine: the “invisible hand” was reframed as a self-correcting market mechanism capable of coordinating economic life without significant government oversight.

When a Metaphor Took Over the Marketplace

Perhaps it is a little like the old game of telephone. A simple message begins its journey clearly enough, but as it passes from one person to the next, it changes shape. By the time it reaches the far end of the circle, it may sound almost nothing like it did at the start. Adam Smith’s meaning drifted in much the same way—what began as a modest, careful idea slowly became something else altogether.

Below is a brief summary of the rise of the gospel of the invisible hand

A Timeline

1950s–1980s — The Birth of a Gospel

In the lecture halls of Chicago. Milton Friedman stood at the podium and promised freedom through the market’s invisible wisdom. In Capitalism and Freedom (1962), he took Adam Smith’s quiet metaphor and turned it into a moral creed: if everyone simply chased their own gain, the world would somehow prosper. It was a bold, elegant idea—and it spread like wildfire.

“Smith’s great achievement—as Hayek and others have pointed out—is the doctrine of the ‘invisible hand,’ his vision of how the voluntary actions of millions of individuals can be coordinated through a price system without central direction.”

— Milton Friedman (1978)

Soon Milton Friedman carried Smith’s ideas into a new age—one of television debates, stock tickers, and rising corporate power. He taught that if we simply let the free market run its course, it would set us free. Many came to believe that the common good would somehow take care of itself, as long as each person and business just chased their own edge—not out of moral duty, but through self-interest alone.

1980s–The Age of the Market

By the 1980s, Reagan and Thatcher were preaching it from the podiums of power. Deregulation became liberation; profit became patriotism. The invisible hand was no longer a metaphor—it was a miracle.

The world was glowing with confidence. Skyscrapers rose, stock tickers pulsed like heartbeats, and boardrooms buzzed with certainty that the market knew best. In 1981, Reagan hailed “the creative energy of the marketplace,” while CEOs quoted Adam Smith to frame greed as civic duty.

Movies like Wall Street turned Gordon Gekko into a modern prophet—his sermon, “Greed is good,” echoed through the decade.

Over time, the “invisible hand” stopped being a metaphor and started being a mantra—one that quietly reshaped how nations write laws, how businesses defend power, and how ordinary people come to see greed not as a vice, but as a kind of virtue.

Many came to believe that this invisible hand explained how both the economy and society stay balanced—how everything somehow falls into place without government interference. By the 1980s, entire mathematical models were built around it. Terms like Pareto optimality and market efficiency gave the metaphor a scientific sheen, as if Smith’s simple image had evolved into a natural physical law.

Mainstream media began to adopt it

The Economist Magazine (1988)

“The invisible hand is the most powerful coordinator of economic life that has ever been conceived.”

— The Economist, late-1980s editorial stance

1990s -

Over time, By the late 20th century, the “invisible hand” became much more than a passing image—it turned into a grand symbol for how order supposedly emerges on its own. Economists began to link it with lofty words like equilibrium, coordination, self-regulation, and harmony. The metaphor entered mainstream U.S. policy language.

By the late 1990s, the invisible hand was everywhere—from political speeches to corporate mission statements. Even when the U.S. repealed the Glass–Steagall Act in 1999, dismantling the barrier between investment and consumer banks, few saw danger. The markets, they said, would self-correct.

New York Times Commentary (1996)

“The invisible hand of the market was treated almost as a divine force, one that would deliver prosperity to all if only government kept out of the way.”

— NYT analyses of Clinton-era globalization debates (mid-1990s)

Alan Greenspan

“The invisible hand has worked to produce remarkable innovation when markets are allowed to function.”

— U.S. Congress, February 26, 1997

(Appears in several financial press summaries of his testimony.)

2000s — The High Law of Prosperity

Over time, the phrase “invisible hand” took on a life of its own. It became shorthand for self-interest and competition—a catchphrase stretched far beyond what Smith ever meant. What Smith once used to describe a narrow, local observation grew into a sweeping creed.

Economists and politicians began to treat it as gospel: that when everyone looks out for themselves, society somehow prospers. From boardrooms to parliaments, this belief spread like wildfire. The “invisible hand” was no longer just a metaphor for unseen influence—it was rebranded as a law of nature, as if greed itself had gravity.

By 2005, the faith had reached its zenith. Alan Greenspan, the powerful Chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, praised Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” as the secret to capitalism’s “inherent stability.”

He believed, as many did, that millions of private choices would weave themselves into harmony. To most of the world, it felt true—homes were rising in value, credit was easy, and Wall Street was humming. People bought second houses, third cars, and futures that looked endlessly bright.

In the process, Smith’s modest metaphor was inflated into a cultural creed—a faith, a belief system that unseen forces keep everything in balance.

The Myth That Markets Alone Can Save Us. What began as a small observation in a philosopher’s book grew into something much larger: with new meaning and almost spiritual in tone, shaping how we see economics, society, and even our own choices.

2008- The Financial Crash

When the Invisible Hand Slipped

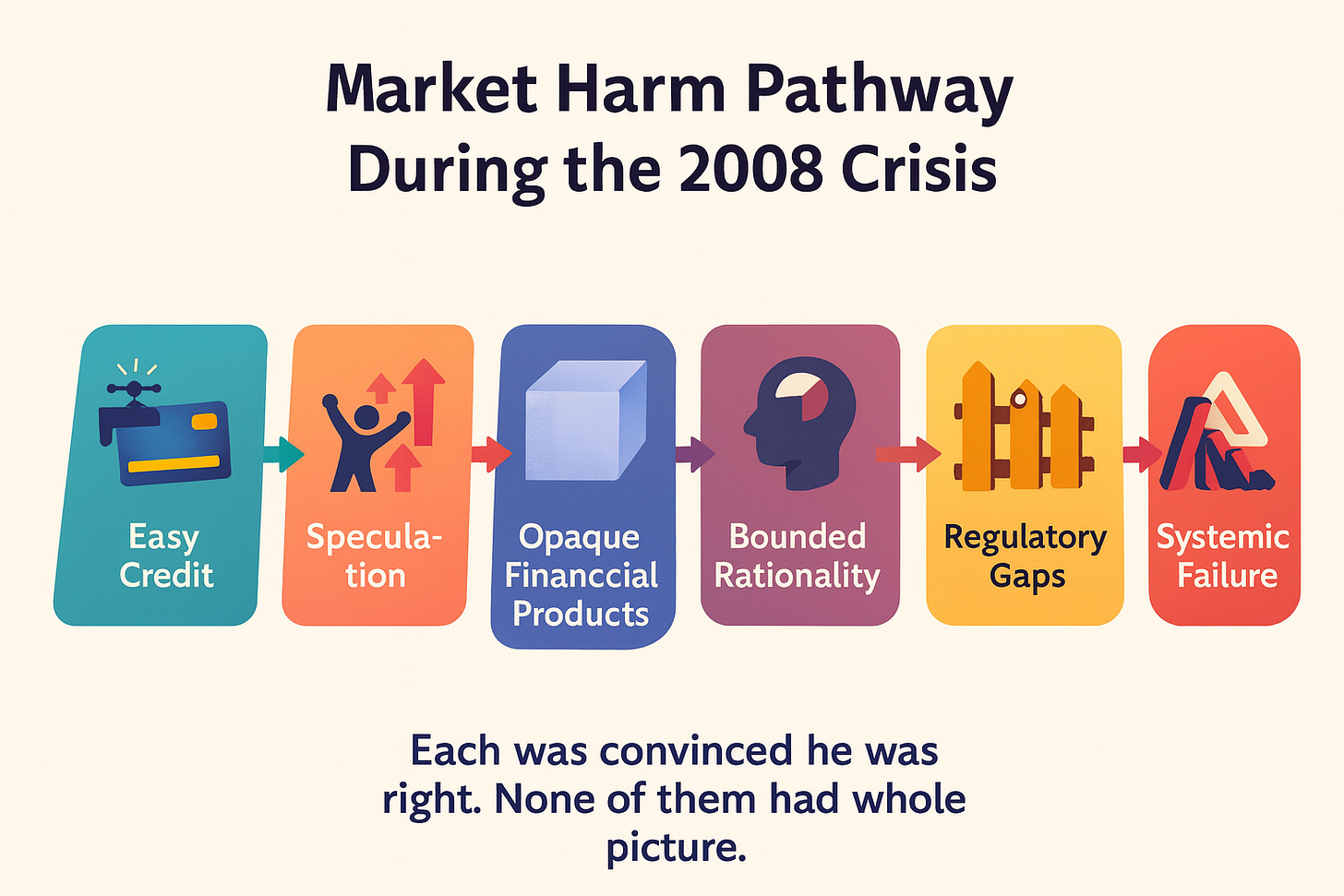

In the years leading up the 2008 financial crisis, the metaphor that once felt steady and reliable began to slip from our grasp. The invisible hand, stretched far beyond what Smith ever intended, could no longer carry the burden we had placed upon it. And like so many of us in that period, it tumbled into the uncertainty and turbulence that followed.

Mortgage-backed securities—those brilliant inventions of financial alchemy—began to rot from within. What had seemed like order turned out to be a pyramid of borrowed faith. The fall was swift and merciless.

Families lost their homes. Retirees watched lifelong savings vanish in a week. Once-busy factories fell silent; office lights flickered out. The invisible hand that was supposed to guide prosperity now seemed to push millions into ruin.

1. Stock‐market collapse — The S&P 500 dropped about 57 % from its October 2007 peak to its trough in March 2009. Federal Reserve History+1

2. Thousands of bank failures — The crisis triggered a wave of bank insolvencies and major bailouts as regulatory oversight failed to contain the risks. Wikipedia

3. Housing‐market crash — U.S. home prices fell, on average, about 30 % from their mid-2006 peak to mid-2009. Federal Reserve History+1

4. Unemployment rate more than doubled — It climbed from roughly 5 % in December 2007 to about 10 % at its peak in 2009. Bureau of Labor Statistics+2Federal Reserve History+2

5. Millions of jobs lost — On average about 700,000 American workers lost their jobs each month between October 2008 and April 2009. Brookings+1

6. Displacement and homelessness risk rose — Families with children, in particular, faced mounting homelessness, driven by job loss and mortgage defaults. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities+1

7. Median household income decline — The real median cash income for U.S. households fell from $57,357 in 2007 to $52,690 in 2011. irle.berkeley.edu

8. Poverty rate jumped — Poverty rose from ~12.5 % in 2007 to ~15.1 % in 2010. irle.berkeley.edu

9. Long‐term unemployment surged — A significant number of those who lost jobs remained unemployed for a year or more, with lasting earnings losses. Brookings+1

10. Wealth inequality worsened — For middle‐income families, the white-to-black wealth ratio increased from 3-to-1 to 4-to-1 between 2007 and 2013. Pew Research Center

11. Increased exposure for low-income and high-poverty areas — Families in high-poverty neighbourhoods were hit harder and faced greater risk of losing wealth. Urban Institute

12. Business investment collapsed — Residential private investment fell roughly from $800 billion pre-crisis to about $400 billion by mid-2009. Wikipedia

13. Homeowners with negative equity — By late 2008, roughly 10.8 % of U.S. homeowners (about 8.8 million) were underwater on their mortgages — meaning they owed more than the home was worth.

14. Worsened mental health outcomes — Studies show that the downturn significantly increased rates of depression, anxiety, and other distress among unemployed Americans and those living in highly impacted communities.

15. Persistent effects on young workers who graduated during the downturn

Research shows that individuals finishing school during the recession entered the labour market with lower earnings, were less likely to marry, and more likely to remain childless later in life. SIEPR

Why it matters: The cost of the crisis isn’t only immediate — it ripples across lifetimes and generations.

Summary

No one meant any harm; meanings simply wandered, as they sometimes do. But over time, this growing faith in the market’s gentle self-correction met the weight of reality—and the meeting was not an easy one. Assumptions that once felt comforting began to crack under pressure. And eventually, these misunderstandings carried real consequences.

As we move into Part 6, we’ll talk about what the crash revealed—and why the invisible hand wasn’t enough to steady the ship. Sometimes a familiar story gives us a sense of safety, even when it no longer matches the world we’re living in. This next part helps us understand that gently and honestly.

Key Points

During the mid-20th century, economists and policymakers expanded Smith’s limited metaphor into a sweeping doctrine: the “invisible hand” was reframed as a self-correcting market mechanism capable of coordinating economic life without significant government oversight.

This reinterpretation—shaped by the Chicago School, popularized by political leaders, and reinforced by media and mathematical models—transformed the metaphor into a quasi-law of nature, treating self-interest and market competition as inherently stabilizing forces.

By the late 20th century, the metaphor had drifted far from Smith’s intent, becoming an ideological creed that justified deregulation and overconfidence in market autonomy, contributing to policy decisions whose weaknesses became visible in the lead-up to the Great Recession.

Footer Navigation:

👉 Next in the series: Crash and The Cost of Blind Faith (Part 6) → (link coming soon)

👉 Back to Part 4 — Lost in Translation → (link coming soon)

🌿 Series Navigation

Read all parts: (link coming soon)

Start from Part 1: (link coming soon)

Next post: (link coming soon)

Previous post: (link coming soon)