The Ethics of Economic Metaphors: Lost in Translation (Part 4)

How Smith’s quiet observation grew into a global doctrine.

Series Note:

👉 This post is Part 4: Lost in Translation for my 9-part series The Ethics of Economic Metaphors.

You can read all parts here → (link coming soon)

Lost in Translation: How Smith’s Meaning Drifted

A Metaphor Grows Beyond Its Roots

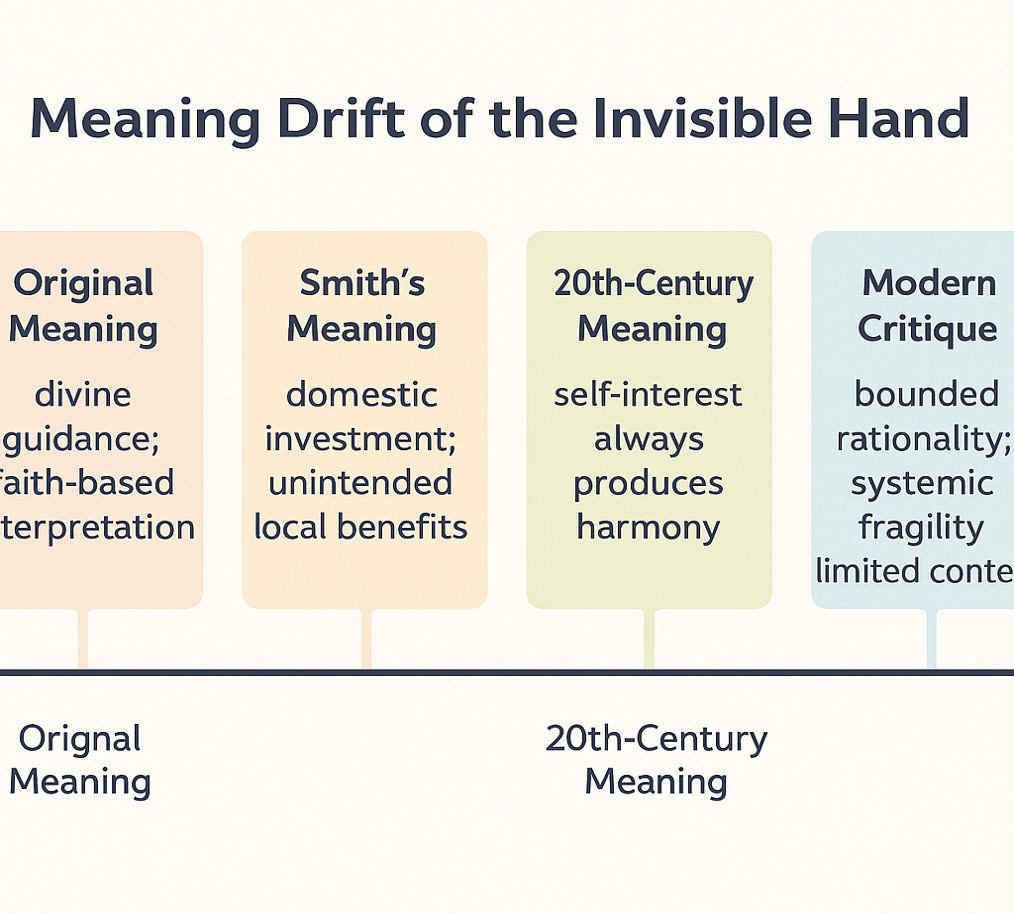

Every idea, if it lives long enough, gathers dust from the roads it travels. Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” is no exception. What began as a modest phrase—almost a whisper in his work—gradually took on new meanings, new purposes, and eventually new contradictions. The metaphor expanded to serve interests Smith never imagined, and in many cases would not have agreed with.

Perhaps none of us noticed the shift while it was happening. But as with many old sayings, the change became clear only when we placed the original beside its modern reflection. What Smith intended as a small, patriotic warning has since been repurposed as a rallying cry for laissez-faire markets. A hand that once pointed homeward now waves across the globe.

A Gentle Recap of Smith’s Original Meaning

Before we go any farther, it may help to return, just for a moment, to the heart of our earlier discussion.

There is a simple truth—offered here with no scolding, only with clarity:

Adam Smith used the phrase “invisible hand” only once in The Wealth of Nations, and not at all in the way it is most often retold today. My intention is not to correct anyone, but to bring the idea back into focus, the way one might gently clean the dust from an old lantern.

Smith’s invisible hand was never meant as a rallying cry for blind faith in markets. It was a small, careful observation about merchants who preferred to invest close to home—where their efforts naturally strengthened their own community, and in time, the wider nation. It was loyalty at work, not license. A soft reminder that prosperity often begins by tending the soil beneath one’s own feet.

For Smith, the invisible hand can guide toward the common good only when self-interest is held within the frame of conscience, responsibility, and care for one’s community. That is the quiet heart of the idea.

The evidence for this original meaning can be summarized in one humble thought:

Self-interest contributes to the public good only when it grows inside the boundaries of justice, care, and moral responsibility.

This is the spirit in which Smith wrote—and the spirit in which we continue our reflection here.

How the “Invisible Hand” Became Something Else

A Quiet Phrase Suddenly Becomes Loud

In the century after Smith’s death, the phrase remained almost silent. Between 1816 and 1938, few authors used it at all. Then, almost without warning, it surged back into public life. Economist Warren J. Samuels found that beginning in the 1940s, references to the “invisible hand” multiplied rapidly—doubling every few decades. By the 1980s, it appeared more than six times as often as before.

This rise coincided with the growth of neoclassical economics. Thinkers like Paul Samuelson, A.C. Pigou, and George Stigler gathered around the metaphor and breathed new life into it. Bit by bit, they transformed Smith’s small observation into a grand symbol—one that seemed to promise that self-interest alone could guide entire economies toward harmony.

Over time, what Smith wrote as a modest insight became an entire worldview.

Entangling Smith with Laissez-Faire

A Marriage of Ideas Smith Never Made

As decades passed, the “invisible hand” became tangled with another phrase: laissez-faire—French for “let do,” or more simply, “leave it alone.” The two ideas fused into one story: that markets flourish best when government steps aside entirely.

A Canadian journalist wrote in 1996:

“Adam Smith’s laissez-faire prescription for a much different economy of two centuries ago is now on trial in this country… If this is true, the best thing for government to do is to stand back and let the invisible hand do its work.” — McGillivray, 1996

It is a neat story. A reassuring one. But it rests on a misunderstanding.

Smith never asked governments to stand aside altogether. He believed deeply in liberty, yes—but in liberty paired with duty, fairness, and public care. The laissez-faire script was written by others—Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, politicians, commentators—not by the Scottish professor whose name has been borrowed so freely.

Smith’s True Concerns: A Patriot First

Freedom, But Only in the Company of Wisdom

Adam Smith believed in markets because he believed in human creativity—our ability to build, trade, and improve our lives. But he was also clear-eyed about human weakness. He knew that the very ambition that drives innovation can also distort justice if left unchecked.

He warned that merchants, given too much sway, could twist laws to serve their interests. He cautioned that nations grow fragile when wealth rushes outward faster than it returns. And in a line that remains strikingly clear, he wrote:

“The sovereign ought never to permit any flattering ideas of commercial opulence

to come in competition with the solid ground of national strength.”The Wealth of Nations

To Smith, government was not an obstacle to liberty—it was a steward of it. He saw justice, education, national defense, public works, and protections against fraud and monopoly as essential duties of the state.

His ideal world was not one of absent government, but of wise government.

The Contradictions of Meaning

The Invisible Hand Was Never a License for “Let It Be”

Modern retellings often speak of the “invisible hand” as if it were a universal law of nature—as inevitable and reliable as gravity. But Smith never meant it that way. For him, the phrase described something rare and fragile: a moment when private interest happened to support the public good.

He believed in the power of enterprise, but also its limits. The phrase laissez-faire—“let it be”—is pinned to him again and again, though he never once wrote it. Smith valued freedom, but he believed freedom needed fences, not to stifle growth, but to protect the common good from being trampled by the powerful.

He warned that when the liberty of a few endangers the security of all, it must be restrained by law. He compared such safeguards to fire walls between buildings—simple protections to keep a spark in one shop from burning down the whole town.

Smith was not preaching a world without rules. He was calling for balance, humility, and moral clarity.

The modern association of the “invisible hand” with laissez-faire economics stems from later thinkers and political movements, not from Smith; his writings consistently emphasize the need for institutional guardrails—justice, public works, education, and protections against monopoly and fraud.

When the Metaphor Changed Overnight

A New Story Emerges—Without Its Author

As the 20th century unfolded, Smith’s small metaphor was stretched far beyond its original shape. It came to symbolize a hands-off doctrine Smith never endorsed. Politicians and thinkers pointed to the invisible hand as proof that governments should vanish from economic life, leaving markets to sort everything out themselves.

But Adam Smith himself was not the preacher of that gospel.

He believed in markets with boundaries. Freedom with conscience. Enterprise with responsibility. He cared deeply about the moral heartbeat of society, warning how easily it could be warped by our instinct to “admire and worship the rich and the powerful.”

For him, prosperity meant something broader than private wealth. It meant trade that uplifted communities, strengthened nations, and protected the vulnerable. When money fled overseas unchecked, when power bent policy for profit, when monopoly hardened into privilege, he did not see success—he saw drift.

The Gentle Truth About Smith and Markets

Freedom Works Best When Guided by Conscience

There are thoughtful arguments for complete deregulation and hands-off government—but Adam Smith was not their author. Those ideas came later, shaped by minds like Friedman and Hayek. Smith’s view was quieter and more grounded.

He saw the beauty of markets: their closeness to everyday life, their ability to listen and respond, their encouragement of innovation. He respected the courage of entrepreneurs and traders—the risk-takers who build new worlds. But he also understood the shadows that accompany that courage.

He never trusted merchants to police themselves. He believed that ambition must walk beside fairness. That self-interest, though powerful, can tip into excess. And that justice, public works, education, and responsible governance were essential partners in any healthy economy.

He even said so plainly:

“Such regulations may, no doubt, be considered a violation of natural liberty. But when the liberty of a few endangers the security of all, it ought to be restrained by law.”

— The Wealth of Nations, Book II, Ch. 2

The Moral Gardener

Adam Smith admired freedom, yes—but never indifference. He cherished the lively energy of markets, yet he also knew their limits and their need for steady care. Though the phrase laissez-faire floated around in his own era, he never once leaned on it. Smith believed in liberty joined to responsibility, not in stepping back and hoping the world would sort itself out without a guiding hand.

A healthy economy, to him, was never a wild garden left untended. It was something living—something that needed pruning, watering, and the quiet presence of a moral gardener to keep it from choking itself. Those gardeners, in our day, are the policymakers we elect and entrust with our common wellbeing.

Setting the Record Straight

I am not here to untangle every contradiction the metaphor has gathered over the past two centuries. My aim is simpler: to show how the “invisible hand” slowly drifted into a meaning almost opposite of what Smith intended. Words can travel that way; no one owns them. But Smith would not have endorsed the newer interpretation.

He argued for freer markets, not markets cut loose from conscience. He valued competition, yet he also believed government must step in where markets falter—education, defense, justice, public works, and safeguards against fraud or monopoly.

His metaphor was never meant to bless greed. It was a quiet reminder that self-interest supports the common good only when guided by moral restraint, community, and wise institutions.

The popular reinterpretation obscures Smith’s actual position: markets function well only within a moral and legal framework, and self-interest aligns with the public good only under conditions of fairness, social trust, and wise governance.

And when we forget that, we risk losing our way—as the world did in the years leading to the Great Recession, which we will discuss next.

Key Points

Adam Smith’s idea of the “invisible hand” changed over time. He meant it as a small idea about helping your own community, but later people turned it into a big claim that markets always work perfectly on their own.

Smith believed in freedom with responsibility. He trusted creativity and trade, but he also believed governments must set fair rules so powerful people don’t misuse their influence.

When the metaphor got stretched too far, people misunderstood it. Leaders began using it to avoid tough questions, and that confusion helped cause problems in the economy later on.

Footer Navigation:

👉 Next in the series: When the Metaphor Took Over The Marketplace(Part 5)

👉 Back to Part 3 — Understanding What Smith Meant → (link coming soon)

🌿 Series Navigation

Read all parts: (link coming soon)

Start from Part 1: (link coming soon)

Next post: (link coming soon)

Previous post: (link coming soon)