The Ethics of Economic Metaphors (Key Points)

A Road Map of the Ideas in my Series

Series Note:

👉 This post is a roadmap for my 9-part series The Ethics of Economic Metaphors.

.👉 You can read all parts here → (link coming soon)

A Gentle Map of the Ideas to Come

A Little Note at the Start: This essay runs long—around 20,000 words, or a good hour and a half by the clock. So I’ve set a small summary here for you, like a lantern at the trailhead. If you’re in the mood for the whole journey, feel free to wander on ahead. I’m grateful you’re here.

Part 1: The Limits of Reason: Why Our Minds Reach for Metaphors

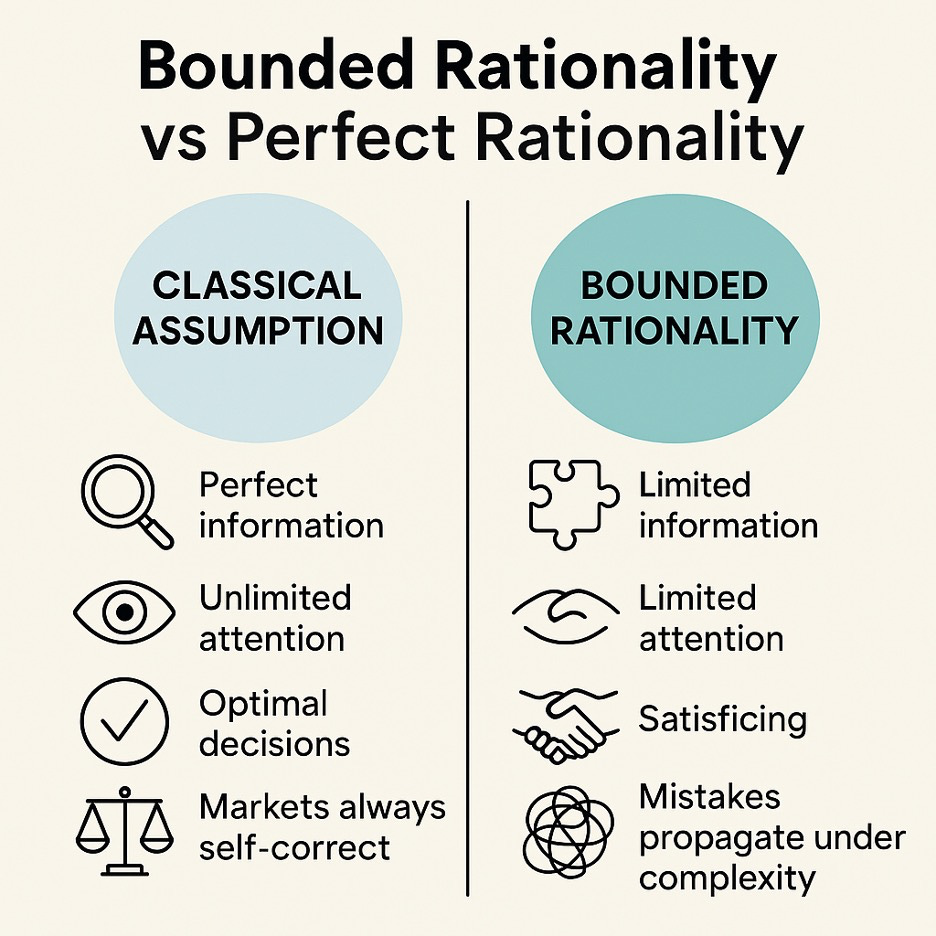

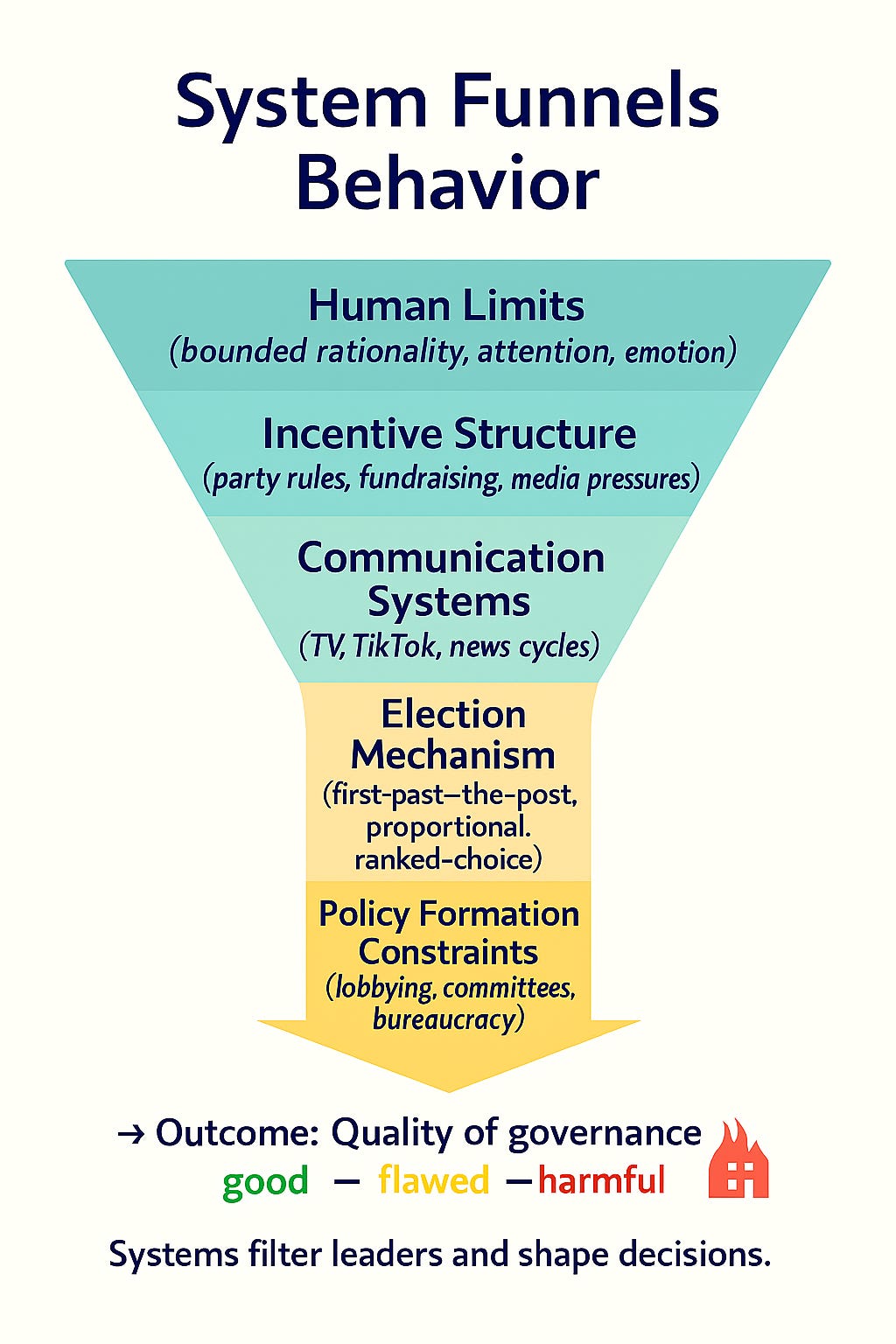

Human cognition is inherently bounded; our attention, memory, and perception yield only partial representations of a complex world.

Because our understanding is fragmentary, we rely on metaphors to organize experience

A metaphor is when you describe something by saying it is something else, to help your mind picture it better.A metaphor is like using a little shortcut for your imagination. It helps you understand something by comparing it to something you already know.

Language helps us organize complexity; metaphors extend that function by mapping the unknown onto the known.

Metaphors offer partial clarity and emotional containment, giving shape to experiences that are otherwise overwhelming.

They endure because they simplify confusion into graspable form, providing both cognitive structure and psychological relief.

Because individuals project their own histories and emotions onto symbolic language, metaphors become unstable and easily stretched, especially in moments of social strain.

In fragile societies, leaders can weaponize metaphors—using simple images to assign blame, divide communities, and justify coercion—turning language from a tool of understanding into a tool of control.

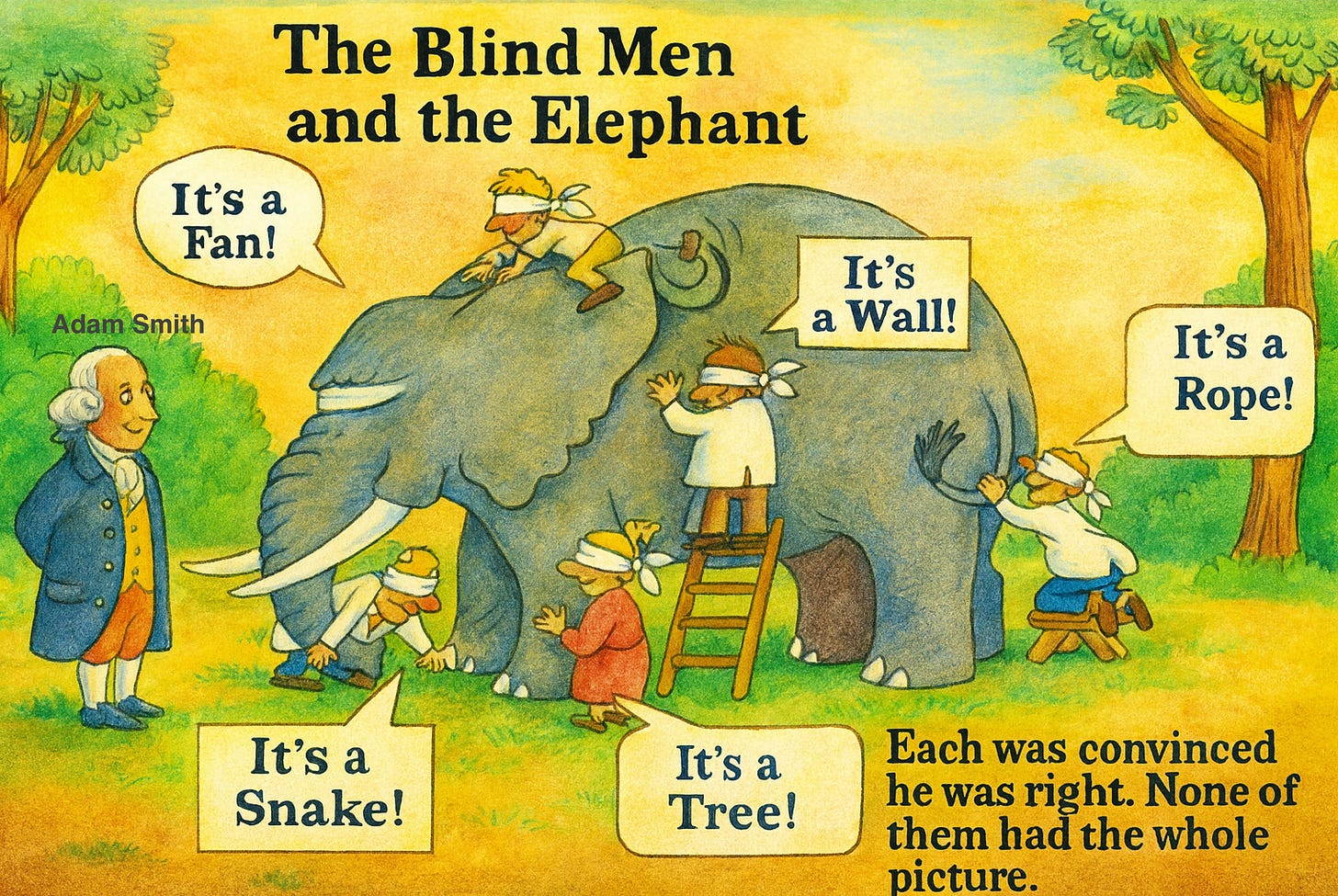

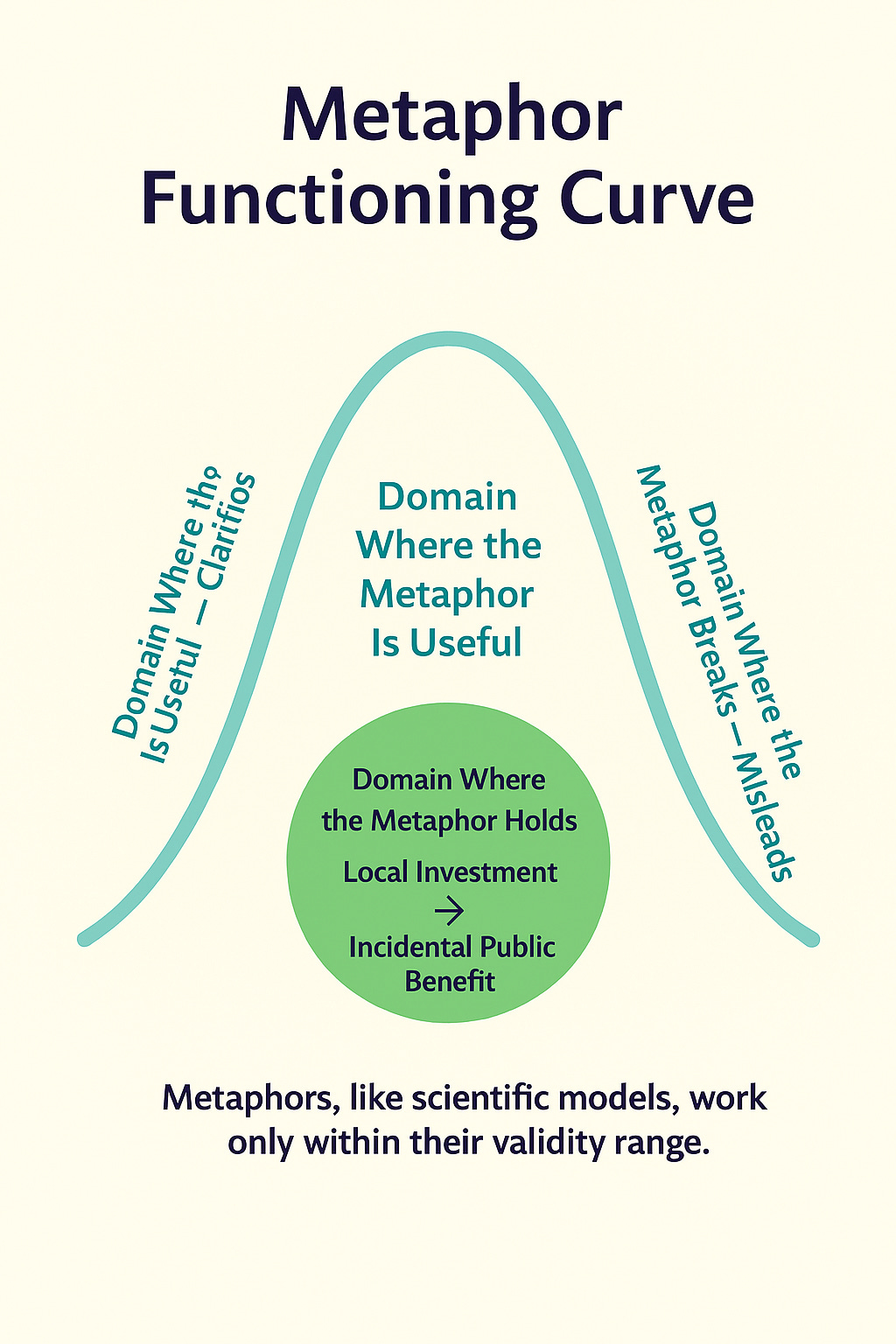

Metaphors help us navigate complexity, but they are partial tools; when mistaken for literal truth, they restrict thought and obscure changing realities.

Part 2: Case Study: History of the Invisible Hand

A case study—using Adam Smith’s own metaphor of the “invisible hand”—will quietly guide us through this problem.

Over time, Smith’s phrase “the invisible hand” has evolved into a cultural shorthand—widely repeated, broadly trusted, and often assumed to describe a natural self-correcting force in markets.

Political leaders, economists, and public figures across eras have invoked the metaphor of the “invisible hand” to support competing narratives: some treat it as evidence of market harmony, others as a myth that obscures the need for institutional guidance.

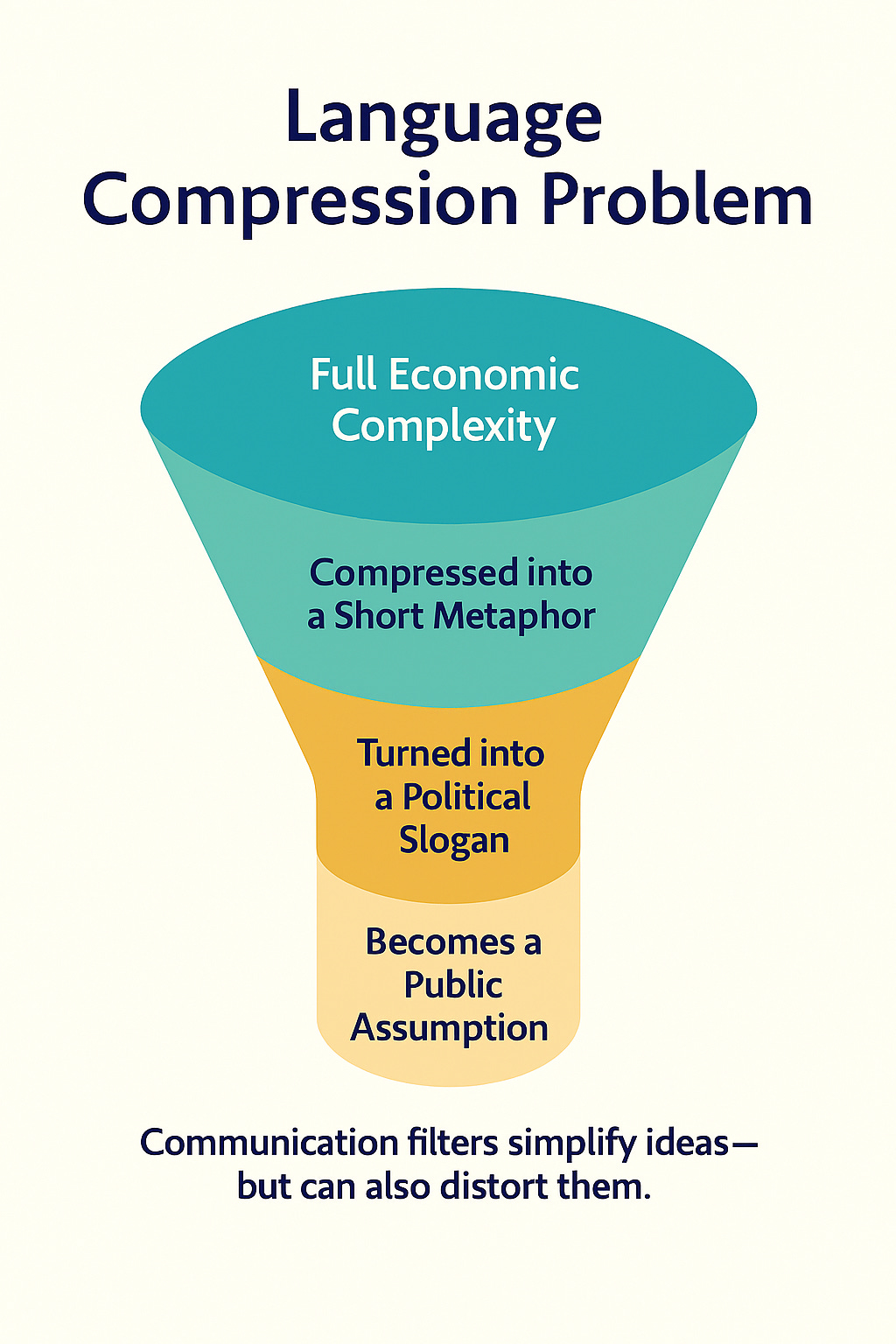

The phrase’s endurance reflects its symbolic power, not its precision; it has become a flexible signifier that people project their beliefs onto, allowing it to justify a wide range of economic and political claims.

The essay does not argue for or against capitalism or government intervention; instead, it examines how systems reflect human limitations. Capitalism is acknowledged as historically effective in raising living standards, but not beyond critique or improvement.

We clear ideological noise and return to first principles—specifically, to examine what Adam Smith actually wrote about markets, morality, and the institutional conditions that make economic systems function well.

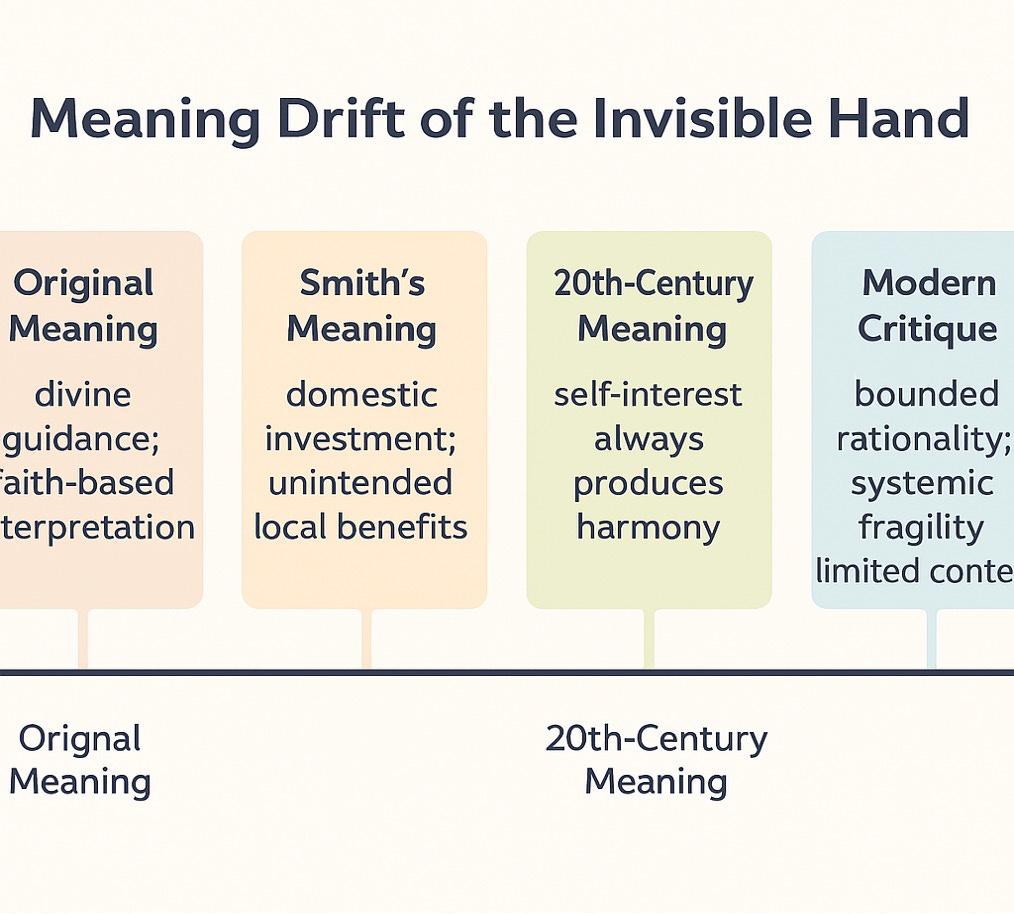

The phrase “invisible hand” predates Adam Smith by centuries; it originated in religious and literary contexts, where it described divine or unseen moral guidance rather than market behavior.

Part 3 – Understanding What Smith Meant

Smith used the “invisible hand” only once in The Wealth of Nations, describing a specific case in which merchants’ preference to invest domestically—out of caution, not ideology—incidentally benefited the nation; it was a contextual observation, not a universal economic law.

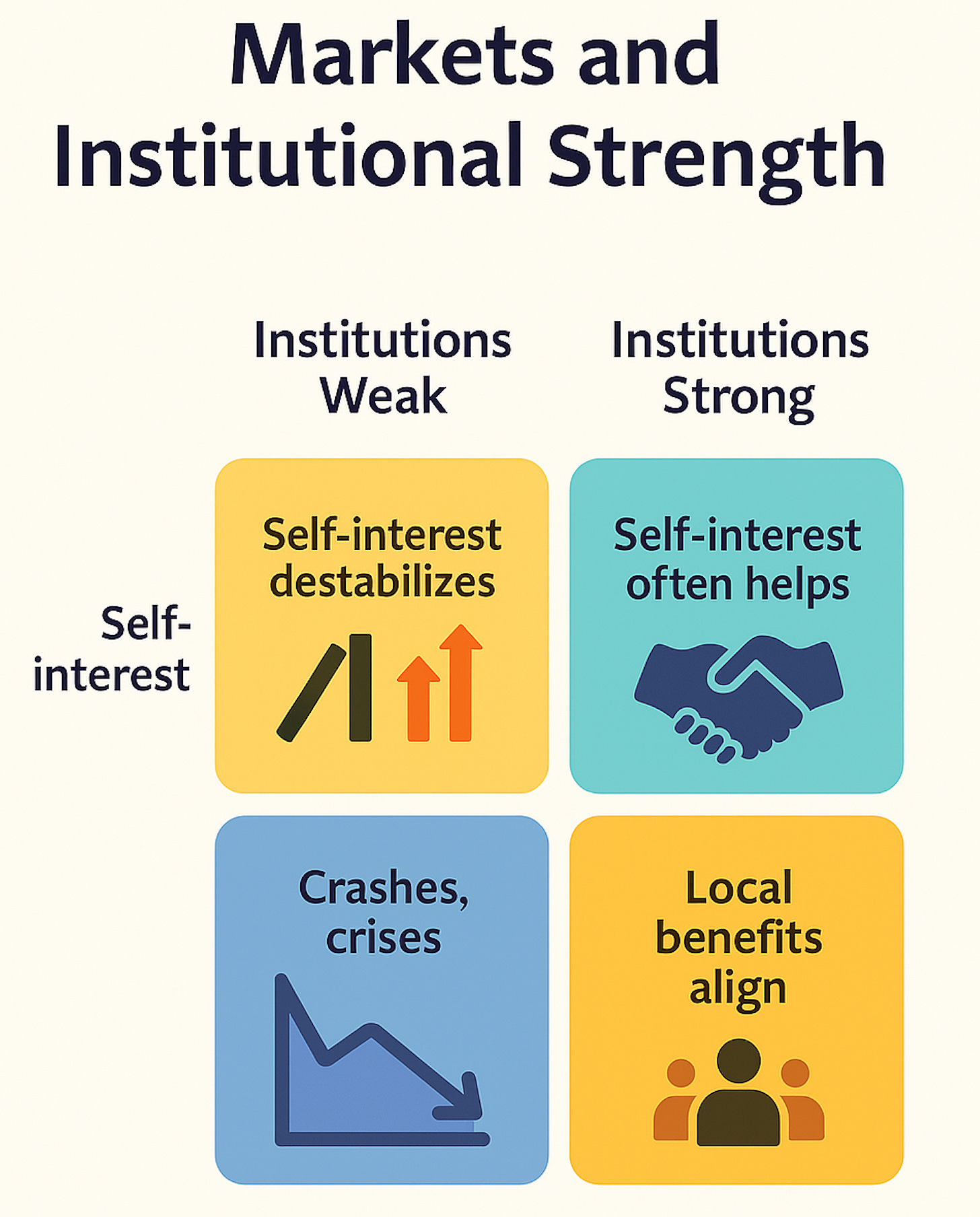

Smith envisioned markets functioning within a moral and institutional framework: the state had essential duties—defense, education, justice, infrastructure, financial regulation—that markets alone could not fulfill. For him, freedom required guardrails, and the alignment of private and public interest depended on ethical constraints, not on invisible mechanisms.

Smith’s “invisible hand” was originally a narrow, context-specific metaphor, but over time it was expanded—particularly in the twentieth century—into a broad doctrine suggesting that self-interest reliably produces social harmony, a meaning Smith himself never endorsed.

Part 4 – Lost in Translation: How Smith’s Meaning Drifted

The modern association of the “invisible hand” with laissez-faire economics stems from later thinkers and political movements, not from Smith; his writings consistently emphasize the need for institutional guardrails—justice, public works, education, and protections against monopoly and fraud.

The popular reinterpretation obscures Smith’s actual position: markets function well only within a moral and legal framework, and self-interest aligns with the public good only under conditions of fairness, social trust, and wise governance.

During the mid-20th century, economists and policymakers expanded Smith’s limited metaphor into a sweeping doctrine: the “invisible hand” was reframed as a self-correcting market mechanism capable of coordinating economic life without significant government oversight.

This reinterpretation— popularized by political leaders, and reinforced by media and mathematical models—transformed the metaphor into a quasi-law of nature, treating self-interest and market competition as inherently stabilizing forces.

Part 5 – When the Metaphor Took Over The Marketplace

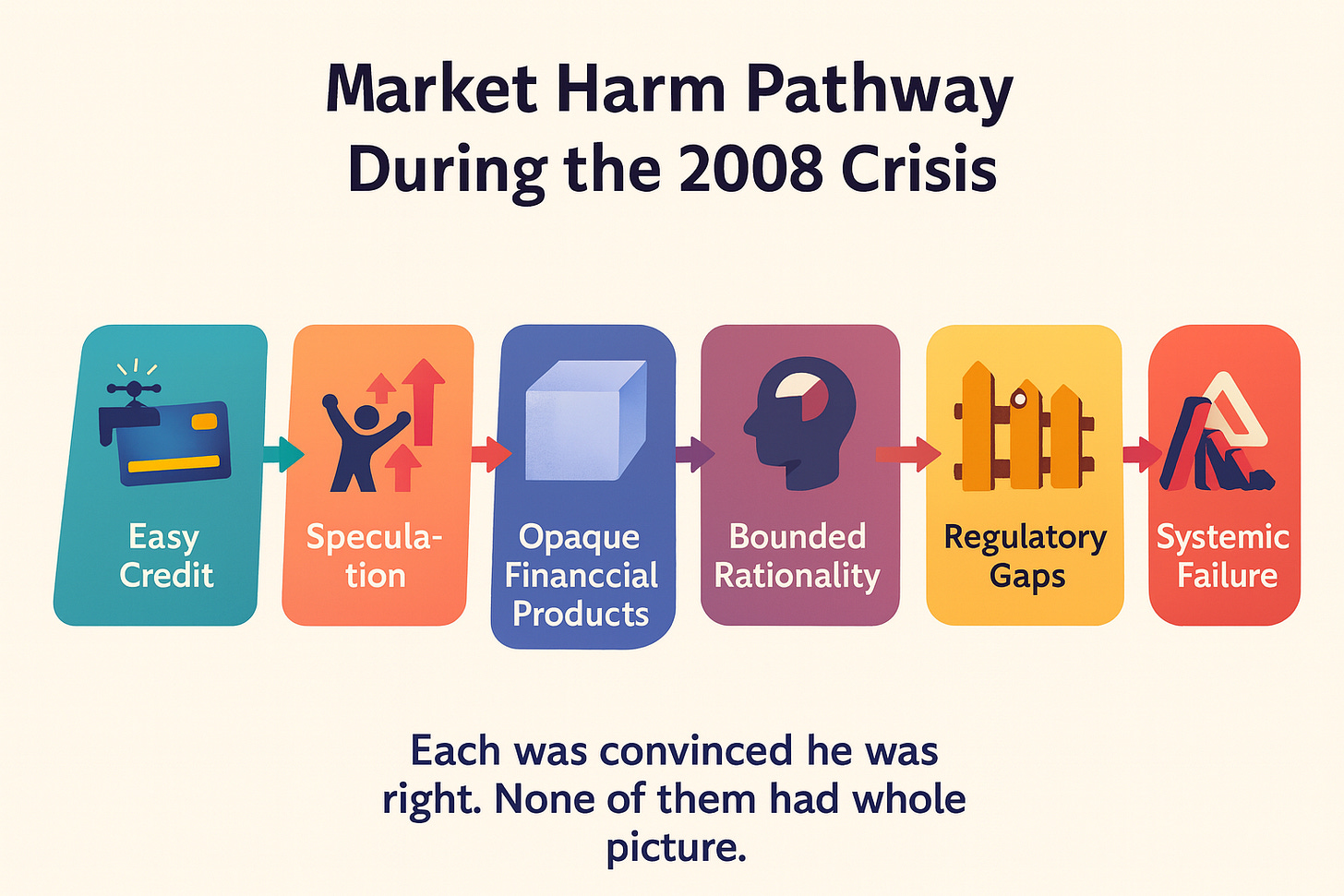

By the late 20th century, the metaphor had drifted far from Smith’s intent, becoming an ideological creed that justified deregulation and overconfidence in market autonomy, contributing to policy decisions whose weaknesses became visible in the lead-up to the 2008 financial crisis

Part 6 – Crash and Consequences: The Cost of Blind Faith in Economic Metaphors

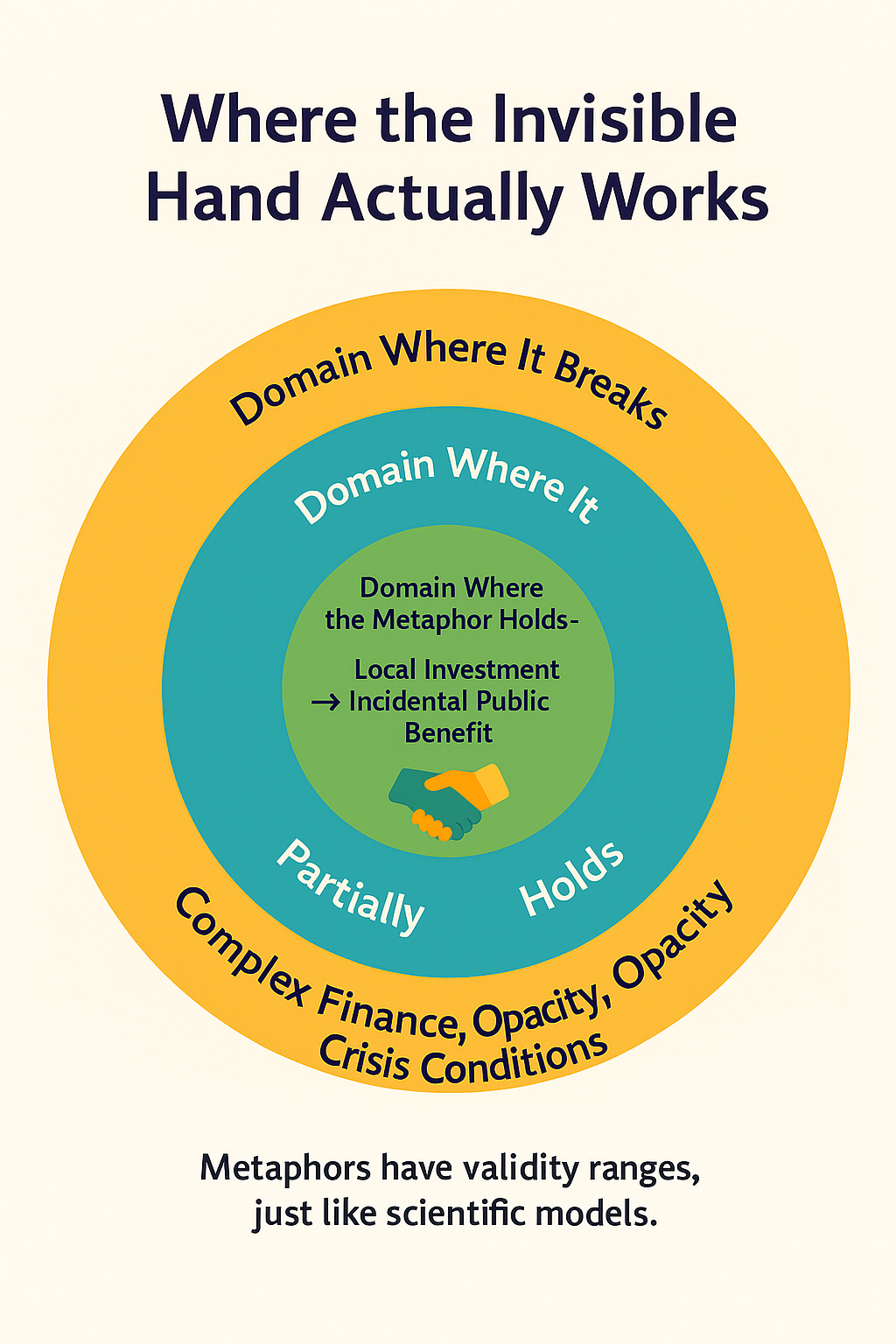

The 2008 financial crisis revealed the limits of treating the “invisible hand” as a self-correcting mechanism; excessive risk-taking, speculative bubbles, and regulatory complacency exposed the gap between market ideology and actual institutional behavior.

The crisis demonstrated that reliance on a metaphor—one that overstated market stability and understated human cognitive and institutional constraints—contributed to policy choices that failed to provide necessary oversight or safeguards.

The collapse underscored that markets are human systems, vulnerable to error and distortion; Smith’s original caution about unchecked self-interest and the need for prudent regulation was ignored, allowing the metaphor to evolve into a comforting myth rather than a bounded analytical insight.

Part 7 – A Recap of How Economic Metaphors Guide Us (and Sometimes Mislead Us)

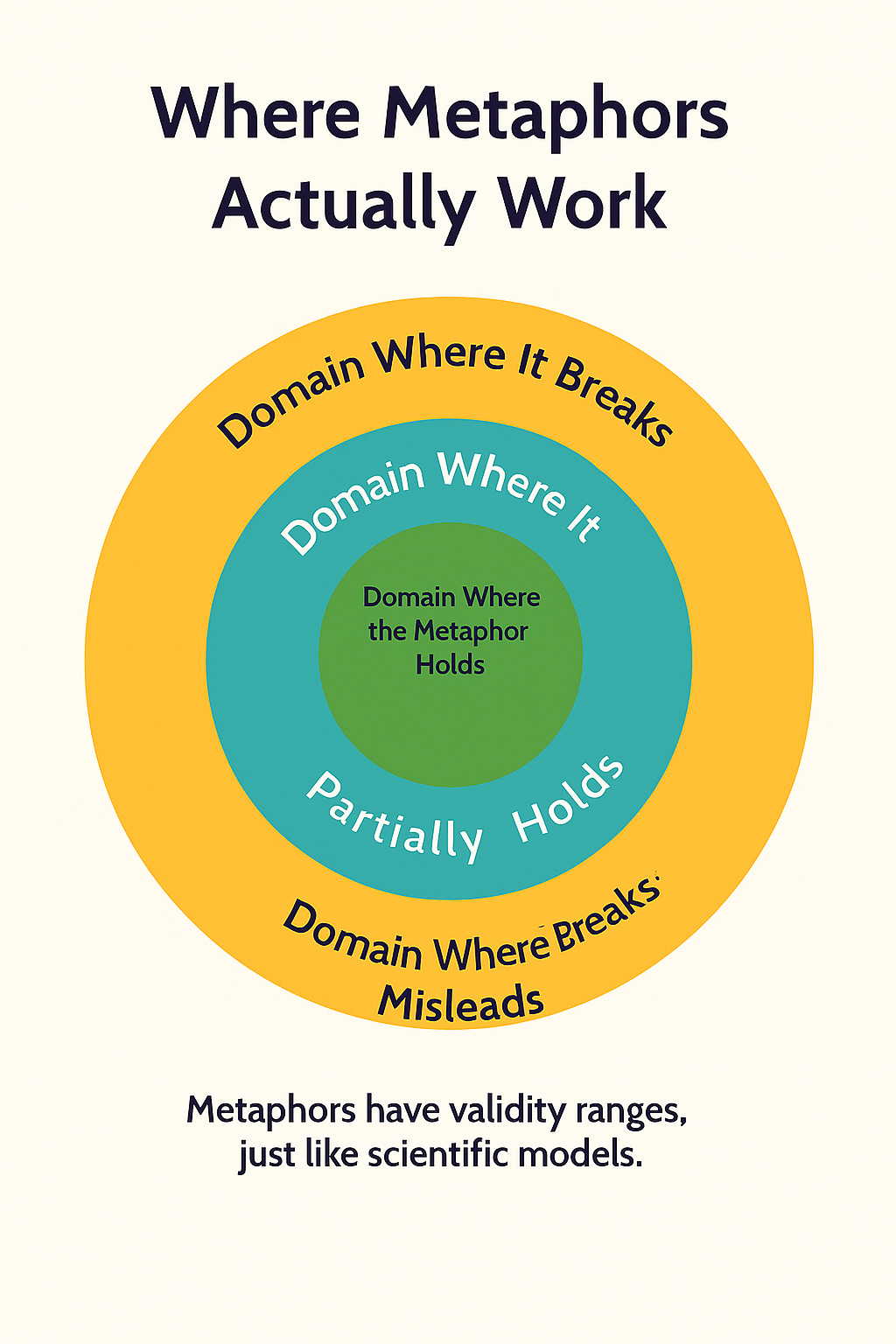

We’re reminded that metaphors evolve as they travel through culture, often expanding far beyond their original intent; because human cognition is bounded, the systems we build—including economic theories—inevitably reflect those limits.

Because human reason and language are both limited, economic metaphors like the “invisible hand” are, at best, simplified models with narrow domains of validity; treating them as universal laws misrepresents reality rather than clarifies it.

Part 8 – What Do We Do Next? The Humble Duties of Public Life

Honesty builds trust. Leaders have a moral duty to tell the truth about where ideas work and where they don’t, so citizens can make fair and informed decisions.

Clarity is an act of care. A healthy democracy requires that citizens receive not only factual information but also clear explanations of the boundaries and assumptions underlying the metaphors used in economic and political discourse.

Citizens also have a responsibility to demand this clarity—asking leaders to define their terms, state their assumptions, and respect the public’s capacity to understand complexity—so that collective decisions rest on transparent reasoning rather than comforting but misleading stories.

Political and intellectual responsibility begins with acknowledging the bounds of human reason. Leaders must use metaphors with humility, recognizing that no single image captures the whole and that interpretation is always conditioned by human constraint.

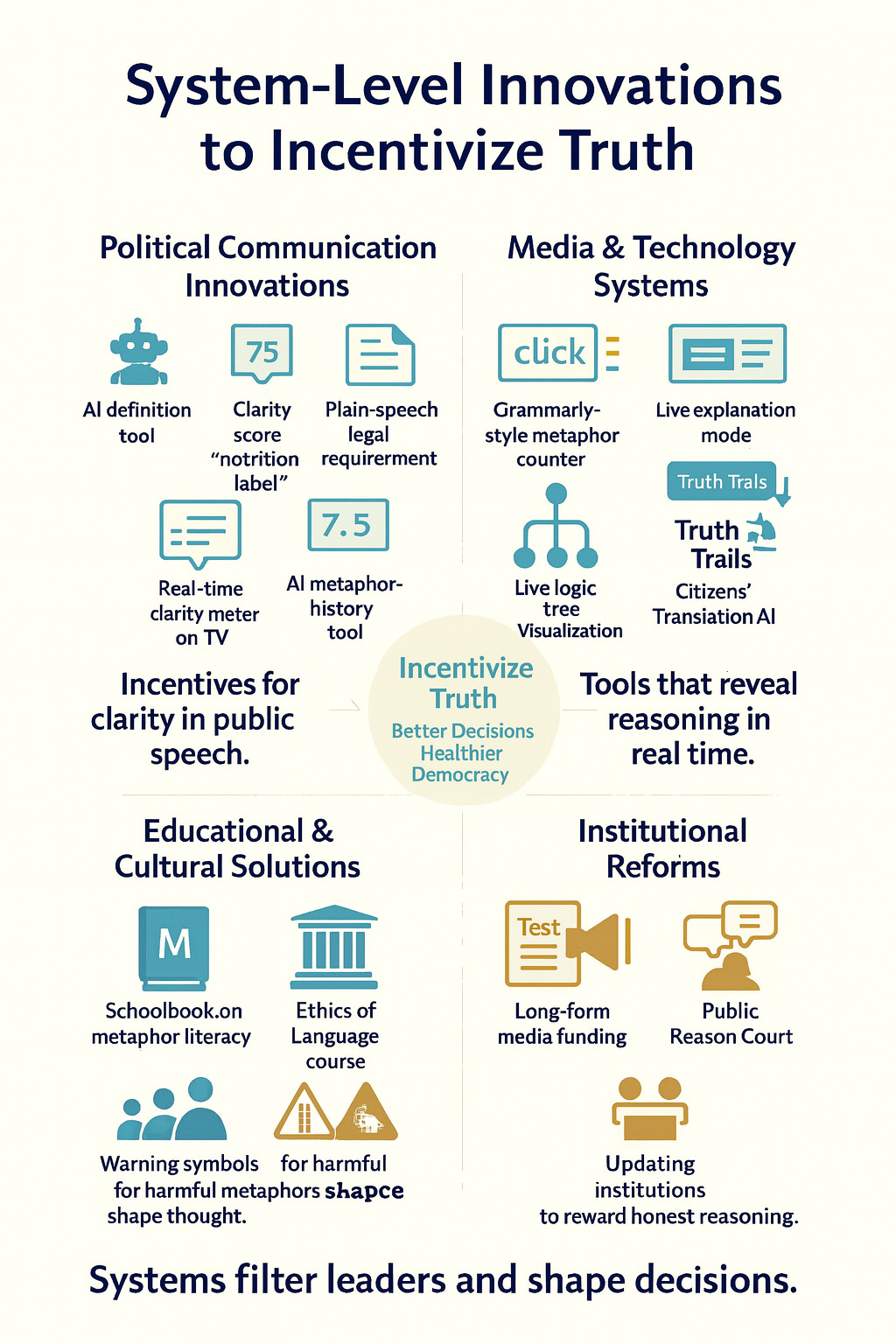

Part 9 – What Do We Do Next? System-Level Solutions

Innovations for a More Thoughtful Democracy

The problem may lie less with individual policymakers and more with the communication channels.

Modern political communication often compresses ideas into brief, metaphor-heavy formats, which encourages oversimplification and obscures the limits of the concepts being invoked.

To restore democratic integrity, political systems must create norms and structures that favor long-form reasoning: plain speech, transparent definitions, and the explicit articulation of a metaphor’s limits.

We present some tools and systems that shift incentives for truth—through AI tools, plain-speech requirements, real-time clarity metrics, and educational reforms—societies can gently steer public discourse toward concrete definitions, explicit reasoning, and transparent argumentation.

A Call for Thoughtful Conversation: Healthy democracies need systems that reward clarity—through longform explanation, transparent terms, and thoughtful public reasoning. When we build incentives for truth, we build environments where better speech leads naturally to better choices.

A Gentle Word on Where I Stand

Before we go any farther, let me set something down plainly, like placing a walking stick by the door. This essay isn’t for or against any grand ideology. I’m not “anti-capitalist,” and I’m not waving a banner for government either. Those labels tend to close ears long before they open minds.

Now, in the spirit of honesty, I’ll say this softly: I do admire entrepreneurs. It takes courage to build something from scratch, to risk failure, to imagine a world that doesn’t yet exist. And yes, capitalism has carried millions out of poverty and into longer, healthier, sturdier lives. That part of the story deserves its due.

But admiration is not the same as blind devotion. Capitalism may be the best arrangement we’ve come up with so far—but that doesn’t mean it’s the best one human beings could create. And government, for all its duties, isn’t always the tool for the job. Often it’s the tinkering minds of ordinary people and businesses that find the wiser path.

Charlie Munger liked to joke, “Just visit your local post office,” to remind us what happens when every corner of life is managed from above. History agrees: when planners try to steer every decision, innovation tends to wither. Shelves go empty not because folks don’t work hard, but because the system forgets how to breathe.

Yet here we stand, in an extraordinary age—healthier, longer-lived, better educated, and less burdened by extreme poverty than nearly any generation before us. That, too, comes from the great engine of creativity and exchange we call capitalism—imperfect as it is, and still evolving, just like us.

📈 Life Expectancy & Mortality

· Life expectancy has nearly doubled (in historical perspective)

In many parts of the world, average life expectancy has moved from ~30s in the early 20th century to 70+ today. (You can find solid data in broader sources like Our World in Data.)

· Global average life expectancy at birth has more than doubled: in 1900 the global average was ~32 years; by 2021 it was ~71 years. Our World in Data+2CDC+2

· The global crude death rate fell significantly: from roughly 17.7 deaths per 1,000 population in 1960 to about 7.6 per 1,000 in 2016. Human Progress+1

👶 Child Survival & Maternal Health

· Neonatal mortality (newborns dying within the first 28 days) has also fallen significantly: globally the neonatal death rate dropped from about 5.2 million in 1990 to 2.3 million in 2022. EBSCO+1

· The global under-five mortality rate dropped by around 61% from 1990 (94 deaths per 1,000) to 2023 (37 deaths per 1,000). UNICEF DATA+1

📚 Education & Literacy

· Literacy has dramatically increased

The global literacy rate rose from about 12% in 1820 to ~87% today.World Economic Forum+1

· Educational access has expanded rapidly, empowering more people than ever before to participate in economy, culture, and public life.

🌍 Poverty Reduction

· Extreme poverty (people living on less than ~$3/day) has fallen sharply: the share of global population in extreme poverty dropped from ~47.1% in 1981 to ~11.2% in 2018. ILOSTAT+1

· According to the World Bank, vast numbers of people have been lifted out of extreme poverty over recent decades. World Bank+1

· According to the World Bank, the share of the global population living in extreme poverty fell from nearly 38% in 1990 to about 8.5% today.

The Spirit Behind This Essay

Yes, capitalism may be the best system we have managed so far. But that doesn’t mean it is the best we will ever build. Progress is like a young sapling—it grows strongest when we tend it with care, balancing enterprise with ethics and innovation with responsibility.

That is the spirit in which this paper is written. Not to tear anything down, and not to prescribe a grand solution. Just to tend the tree a little—to point out a few bruised branches, suggest a bit of gentle pruning, and notice where old weeds may be creeping back in.

What I can say with confidence is this: Adam Smith wrote clearly, and with a moral frame that is often forgotten. Over the years, many have misread him—sometimes innocently, sometimes with purpose—and used his name to support ideas he likely never intended.

So let us begin simply, with three quiet questions:

• How helpful—or harmful—are our economic metaphors?

• What did Smith actually mean by the “invisible hand”?

• And what did he say about markets, responsibility, and the moral footing that holds them together?

That is where our discussion begins.

Footer Navigation:

👉 Next in the series: Part 1 — The Limits of Reason → (Links coming soon)

👉 Back to intro: The Ethics of Economic Metaphors — Welcome → (Links coming soon)

🌿 Series Navigation

Read all parts: (Links coming soon)

Start from Part 1: (Links coming soon)

Next post: (Links coming soon)

Previous post:(Links coming soon)